Written by Jack Ashby, Assistant Director of the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge.

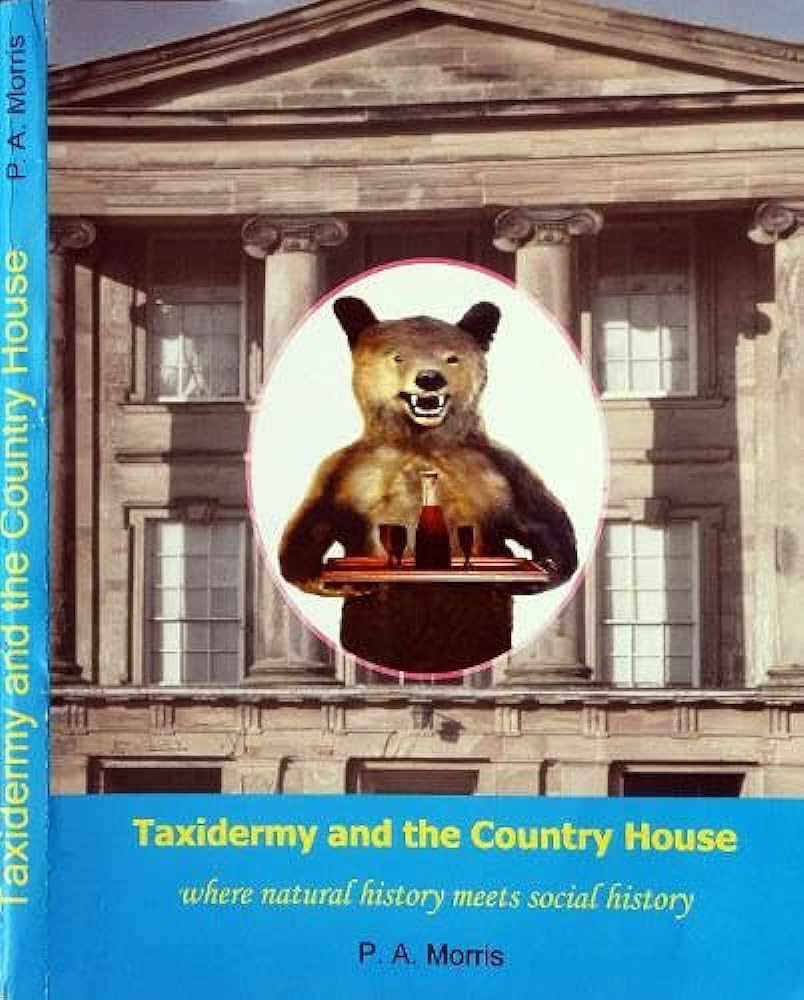

Pat Morris is the authority on the history of British taxidermy, and there is arguably no-one better to write an exploration of the specific context of taxidermy collected for and displayed in private country houses. Although their materiality is identical, by their nature, these collections are often conceptually very different – the antithesis, even – to those in public museum. These differences are not the focus of the book, nonetheless this perspective offers great potential to help us consider more roundly the story of taxidermy and those that made and collected it.

The similarities museum and country house collections do share include their origin-stories, and of course the practicalities of preserving specimens. Like museums, these private collections trace their histories back to cabinets of curiosities. Preservability was fundamental to what could be kept, and Morris begins by explaining that early cabinets of curiosities in country houses were mainly items that required no preservation – dry materials like shells and bone. The only skins that were widely kept were those that could be simply dried without being prone to insect attack, which is why durable specimens like taxidermy crocodiles, hollowed-out armadillos and inflated pufferfish were commonplace in these early collections, rather than the birds and mammals which later became the norm.

Continue reading