Editors note: This is the second of two concurrent blogs about the new diorama at the Booth Museum. Click here to read the first and find out more about how the diorama was created.

Written by Su Hepburn, Head of Learning & Engagement, Brighton & Hove Museums.

Why a new diorama?

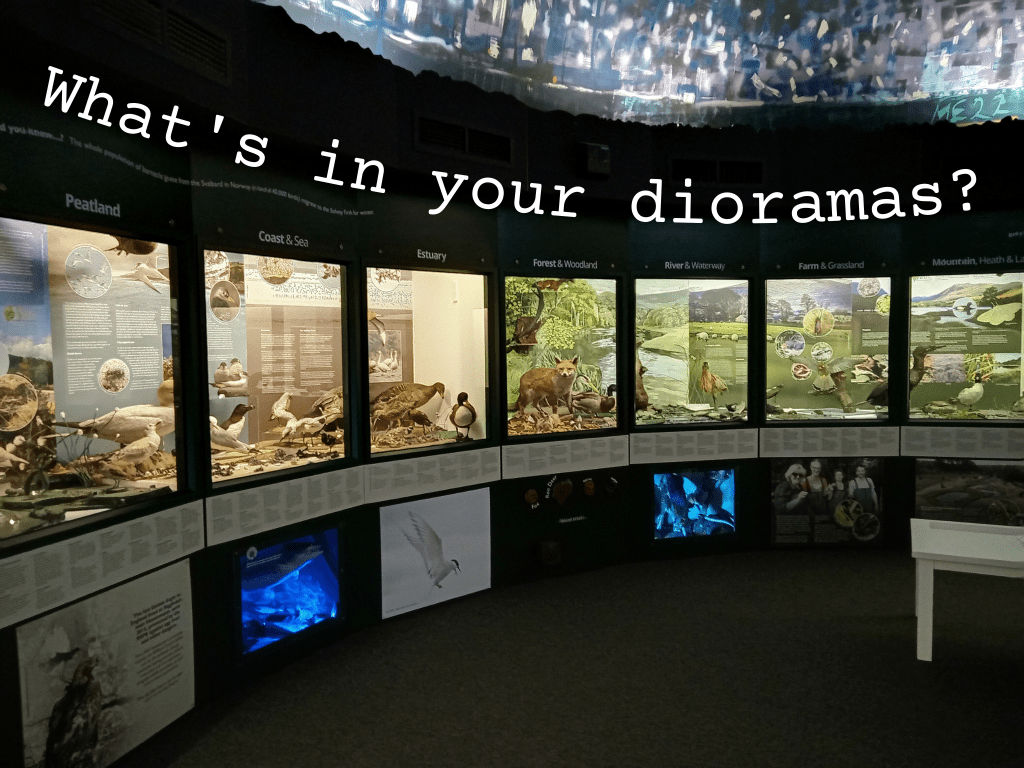

In the autumn of 2022, we started our ‘Discover our Dioramas’ project at the Booth Museum of Natural History, part of Brighton & Hove Museums. Funded by an Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund of £50,000 we set about building the first natural history diorama at the museum in 92 years. This was a significant project for a museum whose Victorian creator Edward Booth had lined every wall with dioramas of birds. Dioramas are an ideal way of storytelling. They are visual and can get a lot of key information to audiences without the need for words.

Alongside this we were also given £3000 from Rampion Windfarms to research and display more information about people especially women involved in the museum’s history.

These projects gave us the time and space to be playful and to make friends. To impact on our audiences, our staff, our collections, and our future practices. It has brought joy to the museum, visitor and staff alike.

Continue reading