Written by Patricia Francis, Natural History Curator, Gallery Oldham.

An account of ‘how to’ reuse an old, forgotten about diorama and turn it into a display highlighting a widespread and major environmental problem of today.

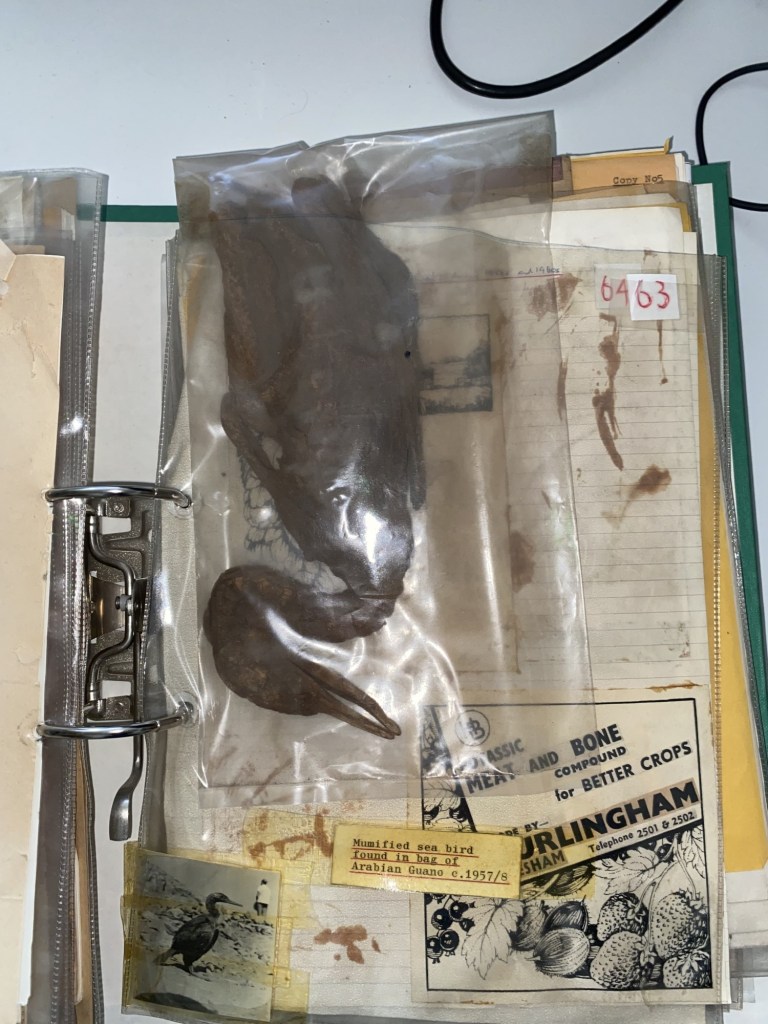

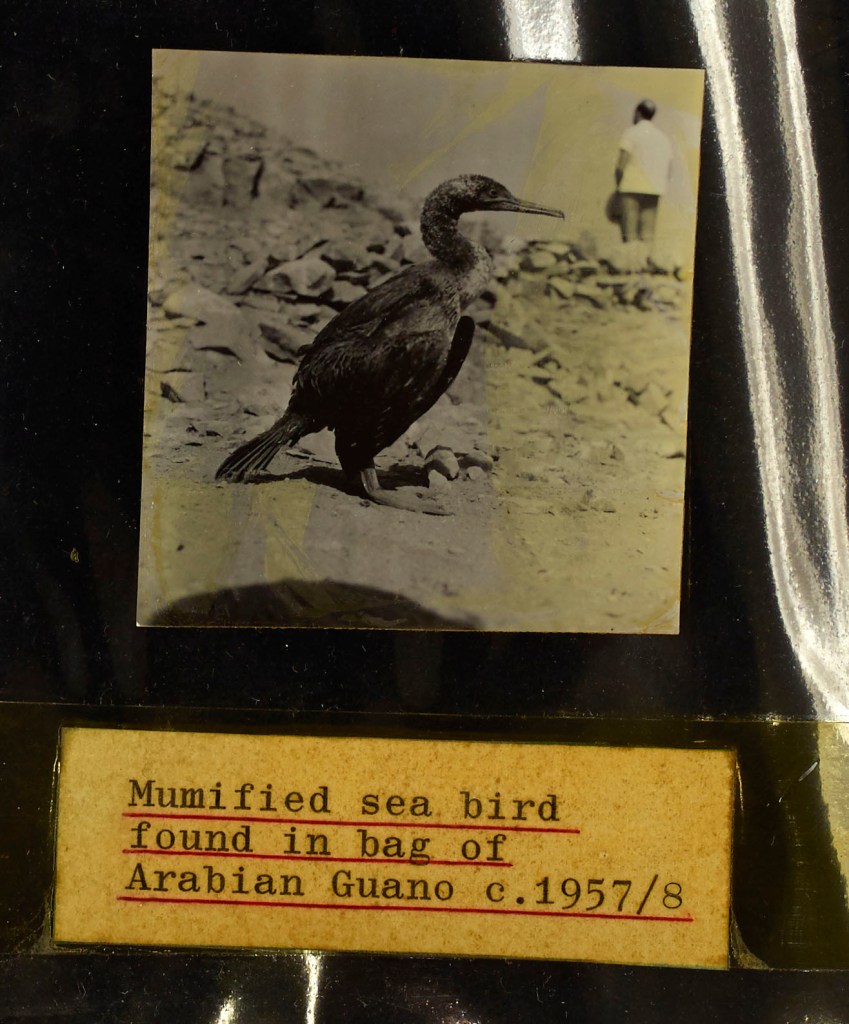

I first found this large sea stack diorama in a corner of a museum storeroom. The storeroom being in a basement of a building without lift access, so the display obviously had had a bit of a rough arrival to its resting place. It had been left uncovered for many years and was in a bit of a sorry state. There were a few birds left in position covered by plastic bags, sad remnants of a previous splendid display. It is a four-sided diorama and on one side at the base of the display is a ‘rock pool’ where a large sea worn pebble bears the following: Fred Stubbs, Oldham 1905.

After a bit of background research, I found this exhibit had four periods when it has been displayed. Firstly, in Oldham’s first Museum which opened in 1883 and where it was made – one of four original dioramas mentioned in a notebook and in the local newspaper the ‘Oldham Chronicle’ in an article of 1909 when it was described as: ‘A splendidly conceived stack, an isolated sandstone rock in the sea…provides accommodation on its ledges for a number of seabirds…makes up a beautiful picture at once artistic and scientific’. At this time a young Fred Stubbs was a leading light in the Oldham Natural History Society. Although the Museum was overseen by the Borough Council, the Society had been charged with the day to day running and creating natural history displays.

Very strangely three of these dioramas were coastal – sea stack, salt marsh and seashore, the fourth was woodland. Quite odd for a town museum like Oldham, far from the sea and where the largest local habitat is the Pennine and Peak District moorland! The maker, Fred, was born in Liverpool – so I wondered if his continued family connections with the coast had influenced this?

Continue reading