Written by Richard Crawford, who has just completed a PhD thesis at the University of the Arts London, entitled ‘Re-presenting taxidermy, Contemporary Art interventions in Natural History Museums’.

Do people read labels in museums? If they do, what do they learn about the object on view? It has been the custom to use labels to give factual names to the things on display in scientific museum displays, but Art curators have taken a different approach and put titles to works that suggest a particular reading of the artwork. These may be suggested by the artist. A good example of this style of labelling is Damien Hirst’s ‘Mother and Child divided’, an artwork that used preserved specimens.

For this work, Damien Hirst famously sawed a cow and a calf in half and exhibited the separate halves in tanks filled with formaldehyde, which he placed apart with sufficient space for a viewer to walk between the two halves of each animal carcass so that they could observe the internal organs of both cow and calf. When it was exhibited at the Tate Gallery in 1995, it helped win him the Turner Prize. The title was ironic. Hirst’s work critiques romantic depictions of the animal as part of harmonious natural order, a place in which mothers protect and nurture their young according to supposedly universal maternal instincts. In place of natural harmony, he presented the viewer with the disjuncture and division brought about by human intervention that brought early death to these two animals, destined for the meat market.

‘Mother and Child separated’, was an early example of a work of Art that used preserved animal specimens usually only encountered in scientific collections, and it established the use of animal bodies as a contemporary art practice. Other artists soon followed Hirst’s example by using natural history specimens in their practice, including Polly Morgan, Claire Morgan, Angela Singer and Tessa Farmer, some of whom went on to exhibit their work in Natural History museums. Each of these artists put titles to their works that suggested a way to read the specimens on display – for instance, a bouquet made up of the heads of dead chicks was entitles ‘Dead Heads’ – suggesting they could be seen as flower heads, but this way of using titles to suggest a particular reading has not been popular in more factually-based museum displays.

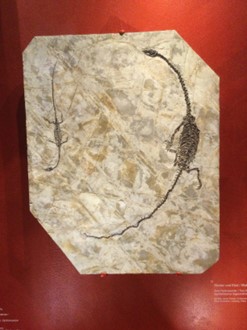

I came across an exception to this rule in the Zoologisches and Palaontologisches Museum in Zurich recently, where I saw an exhibition of fossils entitled ‘Masterpieces of Nature’. The curators of this exhibition had given each fossil on view a narrative title that went beyond established scientific conventions, such as: ‘Mother and Child’, two hydrosaur fossils that had been unearthed in Liaoning, China. The title suggests that a mother-child relationship existed between the fossilized creatures presented in the display, in much the same way that calling a cow and calf carcasses ‘Mother and Child divided’ did. Once this idea has been acknowledged, it is hard to see the two fossils in any other way.

Most of the other fossil displays in the Paleontological collection were labelled more conventionally, such as the “slab with skeletons of the marine sauropterygian reptiles from the Middle Triassic of Monte San Georgio, Canton Ticino”. You can’t go far wrong if you stick to the facts. All the more surprising, therefore that the fossil remains of a bird should be labelled ‘Fly Little Bird’ and a fossil dragonfly labelled ‘Winged Eternity’. A large ammonite cut cleanly into two halves and displayed with the inside face of each visible to the visitor is labelled ‘Divorced’, a title that recalled Hirst’s title of ‘Mother and child separated’ that he used for the cow and calf specimens that he cut in half.

When I saw this exhibition in November, I wondered why the museum had chosen to use the kind of titles that are normally reserved for artworks. The answer was written at the entrance of the exhibition:

“Nature and her muse, evolution, [is] a deeply creative force. Despite having neither foresight nor goal, nature has created beauty to rival that produced by humanity’s finest artists”

The founding idea behind ‘Masterpieces of Nature’ is that Nature is itself creative. This exhibition calls into question the anthropocentric assumption that Art must be created by human agency. The appropriation by the curators of the sort of literary titles that artists give their works confirms the cycle of reciprocal influences that has taken place between Art galleries and scientific museums over the past 30 years – from the appropriation of preserved museum specimens by artists in the 1990’s, to the use of literary rather than literal labels for fossil displays in in 2020’s. Perhaps giving dramatic titles to natural history specimens displays could encourage younger visitors to engage more actively with preserved specimens in Natural History Museums?

Pingback: Art/Science | Pearltrees