Written by Ruth Cowlishaw of Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

This year marks Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine’s 125th anniversary. The school was the first institute of its kind back in 1898, built to help investigate some of the tropical diseases brought back to the busy port city from shipping expeditions and trade. To celebrate such a major milestone an array of events and activities have been planned by the school, including outreach events and fundraising, whilst also giving us a chance to reflect on our history. One such planned scheme was the distribution of internal funds for exciting projects, proposed by staff members that would make a difference in this very special year.

The Dagnall Laboratory situated in the Mary Kingsley Building is the main teaching laboratory for the school. Within its walls it houses many historical pathological and entomological samples, from mosquito wings and blood films to seven-meter-long tapeworms. Throughout the years a selection of these samples has been used to help educate thousands of medical professionals, postgraduate students and armed forces personnel. However, a large part of the collection became forgotten and neglected as specimen preservation skills and staff were lost over time. With news of potential funding myself and the team saw an opportunity to rediscover these “lost” specimens and decided to put together a bid with the aim to reinvigorate our collection. The project not only aligned with the 125 Anniversary theme of Heritage and History but also looked forward to the future.

I’m glad to say that our bid was accepted and became part of a larger project; to conserve, understand and build our entomological specimen collection, the evaluation of historical X-ray slides gifted to the school and the creation of new exciting teaching resources. Now the big question came: “Where do we start?” The answer came in the form of a large storage cupboard in our office, packed with a multitude of entomological specimens. Going shelf by shelf, box by box items were removed and documented, allowing us to finally get a glimpse of what precious resources we had. Many samples were sadly lacking important information such as species, date and collector, but we did the best we could with our knowledge to categorise. By the end over 600 items were discovered, with a mix of wet and dry samples of mosquitos, tsetse flies, sandflies (Phlebotomine), Kissing bugs, ectoparasites and flies, just to name a few.

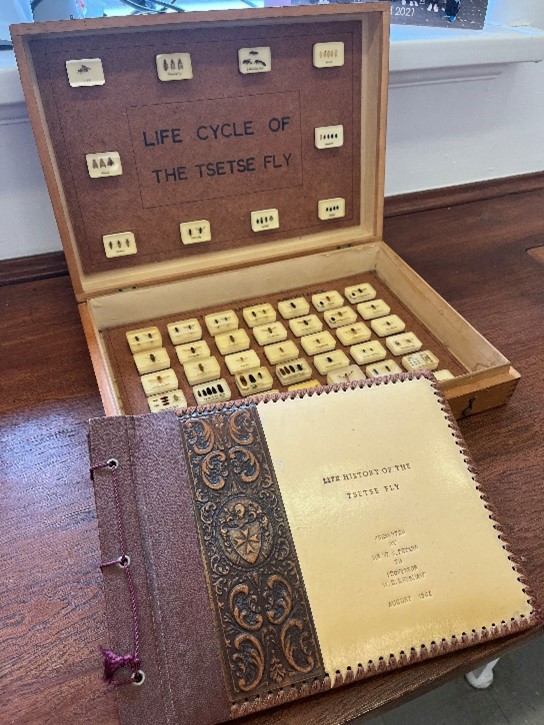

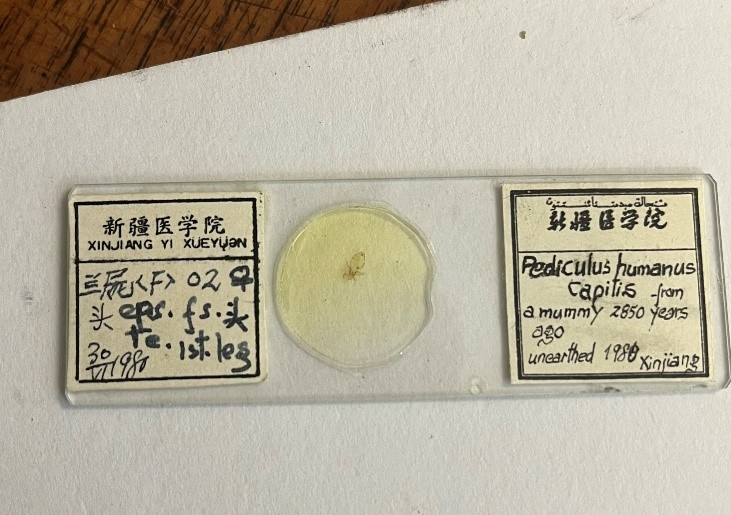

Many of the samples discovered were simple pinned insect specimens in storage boxes, however during our search we found some absolute gems. One such item is a presentation box and matching book on the “Life History of the Tsetse Fly”, presented to Professor W. E. Kershaw by a Mr W. B. Patana in 1964. The book contains many beautiful pictures of the tsetse fly lifecycle, whilst the box has the most wonderful display of specimens encased in resin (see picture above). This find has been incredibly useful to use both in a teaching capacity and to use in public engagement activities. Crowds are drawn in by it’s ‘old school’ feel and historic sentiment whilst also excellently demonstrating the tsetse lifecycle. Another notable find was a microscope slide dated 1980, showing a preserved head louse (Pediculus humanus capitis) from a 2850-year-old mummy in the Xinjiang region of China! It also appears that our previous colleagues had a knack for art – creating the most beautiful drawings of many entomological specimens, several of which are now used in display cases and in teaching sessions.

A handful of the laboratory’s mosquito specimens are currently being used in a National Lottery Heritage Fund funded project, entitled “LSTM- Past, Present and Future”. This project was designed by Sci-art practitioners Tom Hyatt and Natasha Niethamer who created the “Tropical Medicine Time Machine”, transporting users through LSTM’s past, present and future research, including themes of vector biology, public health, snakebite and travel health. This piece of work has been on display to the public at the World Museum, Liverpool over several weekends with amazing success engaging people of all ages. Another Dagnall Laboratory item used in public displays is one of our historical microscopes. It forms part of a display in the auditorium of the World Museum introducing Dr Alwen Evans, LSTM’s first female lecturer. She began her work at the school in 1918, researching Anopheline mosquitos (malaria vectors), going on to become a world-renowned expert in the field. During the investigation of our treasures, we were lucky enough to find preserved microscope slides of mosquitos made by Dr Evans herself – one of which can be found amongst this display.

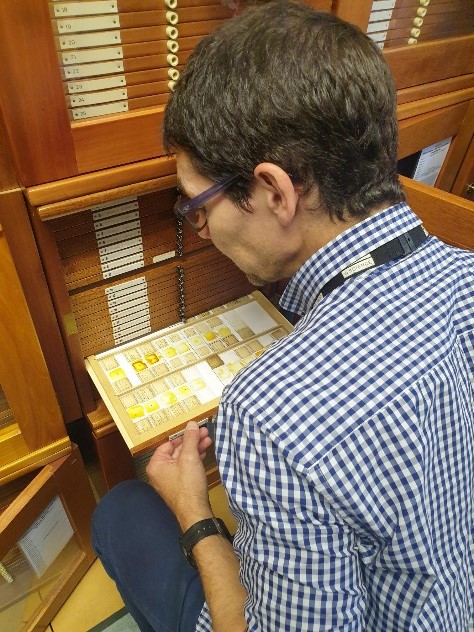

Throughout this project we have worked closely with National Museums Liverpool (NML), relying on their expertise and guidance. We first contacted their team as a large part of LSTM’s entomological collections was given to the museum in previous decades. It was an absolutely amazing experience to go behind the scenes and see how they stored and cared for these most important specimens. I can safely say they had taken much better care of our specimens over the years than ourselves! It was amazing to see all the historical samples in such good condition and it inspired us to do better with ours. Sadly, during the exploration of our own Dagnall Laboratory samples we discovered that many of our specimens had become discoloured by age or had sadly succumbed to pests. Thankfully we could rely on NML’s knowledge again as they kindly agreed to send a group of staff and volunteers up the hill to take a look at our collections and provide us with some advice. The team were absolutely fantastic and we learnt lots from their visit. Many samples were swiftly vacuum packed and put into the freezer in an attempt to stop pests in their track. In August this year we visited the museum again where they provided us with a demonstration of how to pin insects for display. This was crucial for us as a teaching team as many of our entomological samples had become worn and discoloured over the years, reducing their suitability for educational purposes. Our new skills will allow us to pin a new set of insect vectors, providing higher quality specimens for our students.

In the future we hope to build on our success with the entomology samples and move over to our pathological samples for preservation. To ensure materials are conserved for future generations there is also a plan to involve modern technology to create 3D models of disease vectors and scan blood films for teaching purposes. The funding for this project as part of LSTM’s 125th Anniversary celebrations has breathed new life into the Dagnall Laboratory specimens allowing them to continue to educate and enthuse both students and the public in tropical disease research.

Pingback: NatSCA Digital Digest – November 2023 | NatSCA