Written by Jack Ashby, Assistant Director of the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge.

Subhadra Das and Miranda Lowe’s paper, Nature Read in Black and White: Decolonial Approaches to Natural History Collections (2018) acted as a wake-up call to our sector, effectively founding a discipline in natural history museums. In the five years since, a lot of work has begun to address the colonial legacies underpinning collections of animals, plants, fungi and rocks.[i] The principal aims of this work include telling more honest stories about the different kinds of injustice involved in the acquisition of collections; and addressing the fact that our museums have long been prioritising narratives elevating white individuals over everyone else. In doing so, it is hoped that a greater diversity of people will feel represented by our museums, thereby enhancing the relevance of the collections.

Natural history collections dwarf those of any other museum discipline, and unlike sectors which have been thinking about this for decades, the practices underpinning their creation have not traditionally prioritised recording associated cultural or social histories. Like others who felt inspired by Subhadra and Miranda’s call to action, faced with contemplating how to begin to unpick the stories hidden behind literally millions of ‘scientific’ specimens, it was fundamental to consider the question, where do you start with decolonial research in natural history museums? Obviously, there is no one answer, but I thought it could be helpful to list a few possible approaches. One underlying element is to recognise how colonialism and its framings have shaped the way that events took place – from major historical moments to minute individual acts – and how the stories about these events have been told.

Below is a list of possible starting points for research, with examples of what that could look like in practice (in reality most of these overlap). For me, each has something to say about the entwined human and environmental costs of the colonial project – questions that natural history museums are uniquely placed to address.

Historical contexts of collecting

1. Focus on a place

For example, you could pick a former colony and trace stories of specimens that come from that region. This is a good approach if the researcher has expertise in the region’s natural and/or colonial history, as it is likely to lead to questions involving one of the next categories on this list. Over the past two years, I’ve been fortunate to undertake a Headley Fellowship, generously supported by Art Fund, researching the colonial histories of the Australian mammal collections. I started by grouping all our Australian mammal records by collector, and then doing initial surface-level research on each person on the list, searching for signs of power imbalances or violence in their practice; or considering whether they were working with particular species, or at particular historical moments that could open up an interesting narrative.

2. Focus on a person

Once my above shallow dive suggested that there might be more to find, I would dive deeper into an individual collector’s story. For example, by reading several hundred of the archived letters of one of our collectors, I was able to build a picture around how value was placed on Tasmanian animal and human remains by European collectors, and what that meant in the context of how Aboriginal Tasmanian people were being treated at the time [This is being published in Archives of Natural History 50.2 in late 2023].

3. Focus on an event

Are there specimens associated with particular moments in history? This could be specific collecting expeditions, where we are able to delve into how people went about gathering specimens. Who was involved? Are their local or Indigenous collectors who haven’t been given the credit they deserve? How were people treated? Or was natural history collecting a byproduct of completely unrelated events? For example, in our paper on legacies of colonial violence in natural history collections, Rebecca Machin and I explored how a British soldier running a concentration camp in the Boer War was collecting specimens for museums – against a backdrop of events in which over 40,000 civilian lost their lives in these camps, this soldier was hunting birds, mammals and insects “in his leisure time”.

4. Start with a taxon

Is there a story associated with a particular species or group of species? For example, was it described by a person with an important colonial history? Or is there a story around circumstances in which it was first encountered by Europeans? Or is the West’s relationship with it entangled with colonial ideals? As an example of the latter, my book Platypus Matters: The Extraordinary Story of Australian Mammals explores how the way we think of these animals is influenced by a long history of othering Aussie wildlife that started with colonial assumptions that Australia’s animals, people and climate were inferior to that of Europe. Examples like these allow museums to widen the focus beyond individual specimens, and talk about taxa as a whole.

Looking for anonymised collectors

The most positive outcomes of decolonial research include when we learn that a far greater diversity of people were involved in the history of natural history than have traditionally been recognised. The ‘big names’ in the history of science did not work alone, and it does nothing to lessen their accomplishments to say that the people they relied in their work deserve recognition too. Decolonial research is an additive process – it enriches histories, rather than diminishes them.

However, the reality is that it can be extremely difficult to identify who truly collected any given specimen. The main reason is the nature of the power imbalances that underpin the colonial biases we’re hoping to unravel: it was almost always the powerful white collectors that did the recording.

In my experience, specimen labels are almost never helpful in identifying hidden collectors. Just because it says ‘Darwin’ or ‘Wallace Collection’, it doesn’t mean Darwin or Wallace collected them.

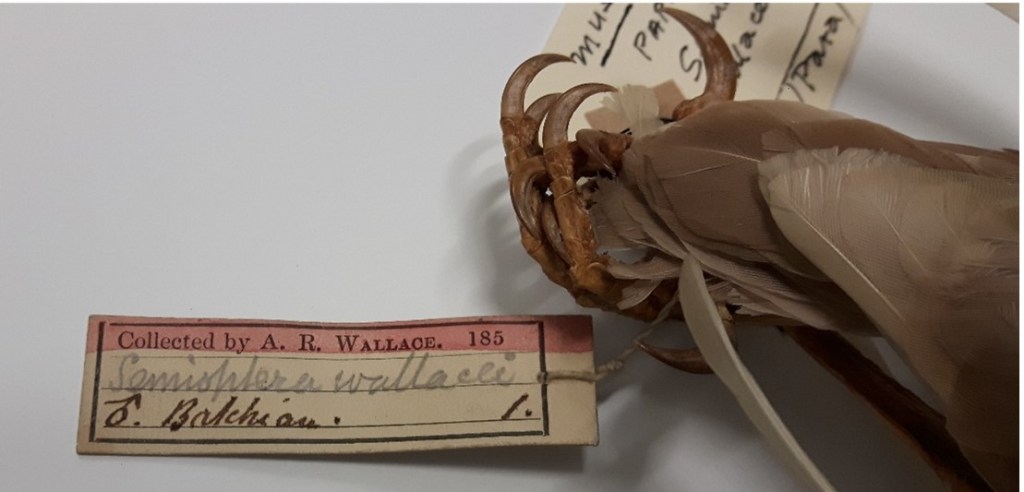

For instance, I can say with some confidence that the type specimen of Wallace’s standardwing bird-of-paradise in Cambridge collected by a 15 year-old called Ali from Sarawak, and wasn’t “Collected by A. R. Wallace”.

And that there’s every chance that this bilby in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History was actually collected by Noongar people from Southwestern Australia, rather than Guy Shortridge or John Bell.

Published accounts of expeditions or species descriptions are similarly unreliable. I’ve come across many examples of museum-based taxonomists thanking their white explorer or settler friends for providing the specimens, when it was First Nations people who truly caught the animal.

Almost all the instances in which I’ve found these “hidden” collectors is in original letters sent from the field, and the references to Indigenous collectors are nearly always incidental. Instead of them saying “Person X gave me this specimen”, you have to read between the lines for mention of something like a third person damaging a specimen when they killed it, or that they had to wait ages for its arrival.

It’s clear from these that no one was trying to hide the truth that they were relying on Indigenous labour, knowledge and expertise, but that the colonial framing in which this activity was taking place automatically assumed that this was not important. Credit was not shared. By diving into the archives, hopefully we can start to fix that.

[i] A collection of resources, including videos from NatSCA’s 2020 conference Decolonising Natural History Collections can be found here: https://www.natsca.org/natsca-decolonising

Pingback: NatSCA Digital Digest – November 2023 | NatSCA