Written by Jazmine Miles Long, Taxidermist. https://www.jazminemileslong.com, Twitter: @TaxidermyLondon; Instagram: @Jazmine_miles_long

For taxidermy to exist an animal must have died. This brutal truth creates unease and leaves the viewer to ponder how the death occurred. And secondly how the death and the body is managed. A fluffy rabbit, cute and cuddly in life, suddenly becomes hideous and untouchable in death. Due to my profession, I am raising a child who has been exposed to dead animals and the concept of death his whole life. This has not made him desensitised to death, I’d say the opposite. He is deeply hurt by the death of any animal; he is a self-proclaimed vegetarian and last week at the age of 4 he asked me if his job when he grows up could be to stop people eating animals. He shouts at cars to slow down in case they hit anything and one of my favourite things he asks me when we meet new people is if they are a vegetarian or a carnivore eyeing them up suspiciously. Does a good understanding of death at a young age give a person greater empathy for animals and take us closer to not seeing them as ‘other’?

When my son is asked what a taxidermist does, he says they look after animals when they die. I get at least one phone call a week from someone mourning their dead pet, I give advice on what to do next, ideas for memorials and how to store the body in the freezer while they decide what to do. I didn’t expect as a taxidermist to be a councillor, a listening ear, someone who is qualified to talk about death.

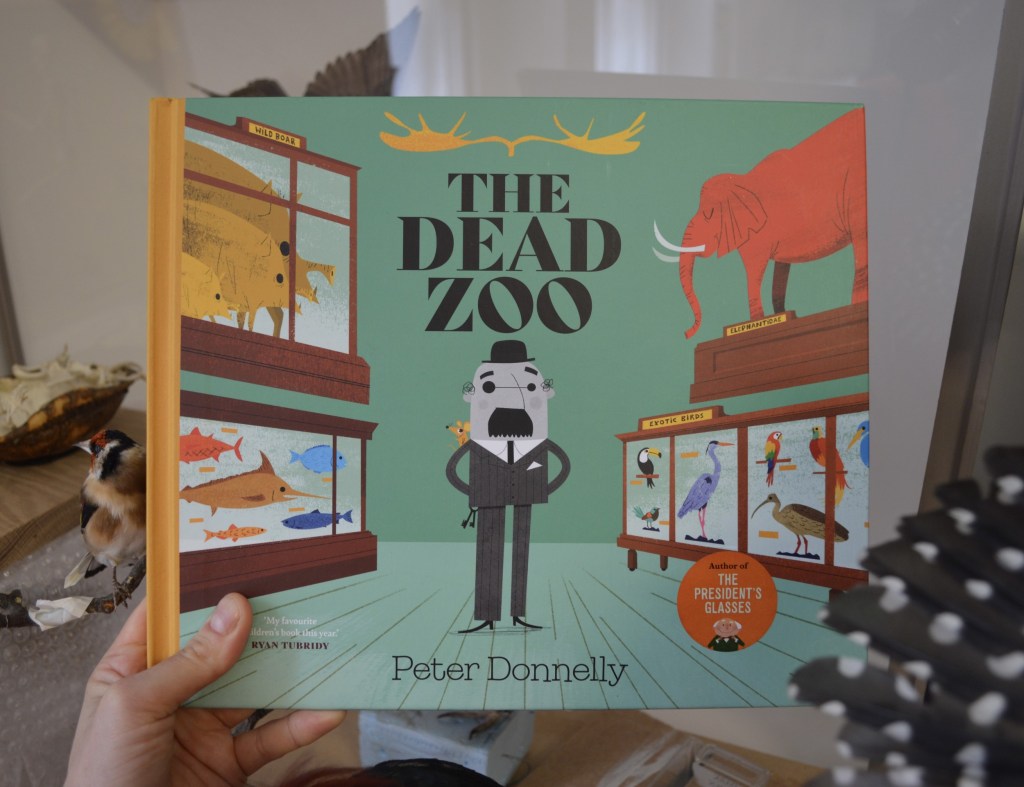

Last April I ran a workshop at Hastings Museum for pre-school children and babies. We called the event Dead Zoo as I read from the book ‘The Dead Zoo’ by Peter Donnelly which was inspired by the National Museum of Ireland’s Natural History Museum. When we were writing the title to advertise for the workshop on the website we didn’t know if the word ‘dead’ would put off parents, but the event was very quickly fully booked. When we talk to children about death it’s often blurry and vague but maybe through talking about the death of animals, we can explore more gently the harsh reality of our own unavoidable demise. And hopefully the realisation that animal life is fragile and has an end, will sow the seeds of respect for nature and a need to protect our planet.

The first question I get asked by children when delivering workshops is ‘Did you kill it?’ And I can understand why they would ask this; taxidermy’s history is entwined with hunting and colonialism and therefore does (rightfully so) have a bad reputation. Almost every movie villain has taxidermy on their wall or is a taxidermist themselves. It is important for me to show children that I am a taxidermist and not this stereotypical serial killer/bad guy/villain and that I only work with animals that have died from natural causes.

There is an assumption that the process of taxidermy is grotesque and dirty, sifting through layers of blood, guts, and flesh. However, skinning is only a small part of the taxidermy process which is a delicate and highly skilled craft. It is a relationship between the animal’s body and the maker. This relationship can of course be harsh and heavy handed, but it can also be tender, meaningful and beautiful depending on the approach.

As a taxidermist it is a true pleasure to be in the presence of a body. To have the opportunity and privilege to be so close to an animal in death that I could not see in life. Each species is unique, and I am an explorer. Like the first time I lifted the facial disk on a barn owl’s head to reveal its ear, and to find the most delicate feathers unfolding like fern curls. It’s moments like these that take my breath away and I do not forget them. I learn through experience. I am not trained as a scientist I am trained as an artist but the bodies I work with teach me their anatomy.

Taxidermy is a series of processes that must be methodically followed to reach the final outcome, it is a craft because you have to teach your hands the skills needed for each stage. As I part the feathers down the breastbone and make an incision, it is careful and slow. I delicately lift off the skin from the body using my fingers to separate skin from muscle, disconnecting them into two separate entities. I carefully clean the skin or tan it depending on the species, and I study the musculature structure of the body and sculpt my own in wood either using a fine soft wood-wool or solid balsa wood. I add detail with paper pulp, plaster, or clay. I observe the body closely taking measurements; I carve, cast, sculpt, and build.

I have been told before that the structures inside are just as beautiful as the final work, but I disagree, for me the sculpture I make is simply mount making for the skin. I sometimes describe taxidermy as upholstery to help others understand that taxidermy is not a process of stuffing (a dirty word for some taxidermists) but instead that it is a process of ‘mounting’, sewing, and fixing the skin onto a form. However, the word upholstery sounds too harsh for the reality of what it feels like to mount a delicate skin. If I’m working on a small animal, I barely breathe so I don’t shake. I am often asked for tips on how I manage to work with such tiny birds but the best advice I have ever been given was ‘if you are calm and your workspace is clean, you will be able to do the delicate work’. When I put this advice into practice, I managed to start mounting up small birds.

When the skin is finally mounted onto the form it is sculpted and manipulated into place, hence the word taxidermy which the Latin translates to ‘arrangement of skin’. The taxidermy is then tended to over a period of time as the skin dries, if it is left to its own devices, it might distort, and feathers and fur might lift into the wrong position permanently. Eventually any exposed skin needs to be painted as the colour pigment is lost as the skin dries. And then the taxidermy is finished.

All of this makes taxidermy sound idyllic or easy, but it can be really stressful. There are lots of factors that can make taxidermy go wrong; decomposition, materials not working as they should, lack of experience and time. However, it is incredibly rewarding when it does go well but when it doesn’t it can be soul destroying. I was running a Children’s workshop at the Booth Museum of Natural History earlier this year, we were creating bind-up sculptures that go inside a taxidermy mammal. One of the children was struggling because he wanted his to be as good as mine even though it was his first ever try. I could see him getting increasingly frustrated with himself, so I told him he would make a very good taxidermist because he had the drive for perfection, but I also told him that my job still makes me cry on a regular basis even after 16 years of practise and it is not for the faint hearted.

Well executed taxidermy is not produced from hate or misunderstanding of the animal, it is made through a love and dedication to the study of animals and years of honing one’s craft.

Although taxidermists all strive for realism as close to the living animal as we can, each has a unique style like a fingerprint on the work. My unique style seems to be adding ‘cuteness’. I have lost points in competitions for moving eyes into a more appealing place and it means I struggle more with some species such as raptors as they have sharp piercing faces. My human error and want to connect and empathise with the animals I work with leads me to anthropomorphise them in a subtle way into becoming more ‘Disney’.

Humans can be selfish and see non-humans as ‘other’. I am generalising here, but we only truly value them if they have some relation to us. We present and categorise taxidermy within museums as science objects, however these objects themselves are clearly more than just natural history. A painting, sculpture, ceramic pot, or item of clothing created by human hands constitutes as art, design, craft, fashion; all objects of anthropological importance and are therefore elevated and categorised as such. A piece of taxidermy is only categorised in this way when the object value is higher than that of natural history, either conceptualised within a fine art context, or when the skin has been used for a practical, musical, or wearable use. Why do we undervalue the craft of taxidermy and those who create it?

I think taxidermy is still widely seen as some kind of magic trick. As if we dip the animals in some chemical in a chosen pose and put them in glass cases. I am often asked if I have to mount an animal in the pose it died in, and I like to visualise a diorama if this were the case. But do viewers see animals displayed in museums in their ‘natural habitats’ as a snapshot of life taken away, posed exactly as they were when they were killed?

If every museum openly displayed how taxidermy is created, from how specimens today are collected to how they are preserved, would this change the perception of the viewer? I definitely see this when I give talks and workshops, as if understanding the process of how these animals came to be in a museum changes their view from passive or cynical to engaged and gives them more to see.

If right now we decided that taxidermy was art and gave it the same value as other crafts, categorising our taxidermy natural science collections within museums also as art would this make it easier to obtain funding for natural science projects and conservation within museums? Or would the fact that taxidermy is still using the remains of an animal continue to keep its value low?

Is there an ingrained prejudice against taxidermy because it is perceived as cruel or is it simply because animals are ‘less important than us’?

I believe that taxidermy is not only useful for science and education but that it really can be used to show the utter beauty of living things. A poignant reminder that life is fleeting and precious and that we need to work hard to protect it. I consider this message alone enough to call it art.

A very nice piece. I work with teachers and will be sharing this with them. These concerns always come up and I think you did a wonderful job with this.

LikeLike

Thank you Jazmine. Very interesting article which will help me explain the taxidermy at Calke Abbey.

LikeLike

Pingback: NatSCA Digital Digest – September 2023 | NatSCA

Pingback: Taxidermy as EcoGothic Horror: Five Questions for Christy Tidwell - Edge Effects

This was such a thoughtful and beautifully written piece—thank you for articulating the deeper meaning and emotional weight behind our craft. As a turkey taxidermist myself, I especially appreciated the focus on the relationship between maker and animal. At Turkey Creek Studios (https://turkeycreekstudios.com), we talk a lot about how every mount tells a story—not just through pose and preservation, but also through the small, intentional details. For example, I include a tiny tick on every turkey mount I create—my little tribute to the wild reality of the birds we work so hard to honor. Thanks again for sharing your insight and perspective.

LikeLike