This post is a late addition to our series of write-ups from the 2015 NatSCA Conference.

FIGHT!

(Twitter notes on discussion Storified here: https://storify.com/Nat_SCA/natsca2015-tweet-along-day-one-morning)

There was an ongoing disagreement between Jack Ashby (of the Grant Museum of Zoology, UCL) and Paolo Viscardi (at the time of the Horniman Museum and Gardens, but coincidentally now also of the Grant Museum) that finally came to a head-to-head debate at the 2015 NatSCA conference. The proposition put forward to frame the debate was: “This house believes that public museums should not charge for filming when the production content aligns with the museum’s objectives”.

As with any debate, there were terms and conditions that needed to be clarified to avoid the argument from becoming mired in semantics or polemics, so it was mutually agreed that filming conducted primarily for promotional purposes (for example, in a programme that was directly about the work of the museum) and filming that only used the museum as a backdrop (for example, in an advert for a fast food restaurant) be excluded from discussion, since the former would be justifiably free and the latter would always be expected to pay a fee.

Round 1: Delivering your mission?

Paolo in proposition

The first point made was that public museums maintain collections for the benefit of their audiences, so where the use of the collections in filming supports the mission of the museum, it allows the collections to reach a wider audience, helping to fulfil their potential. In order for this to be worthwhile the museum should always be named, but need not always be paid.

Jack in opposition

So Paolo is arguing that working with film crews for free is simply another way of delivering a museum’s mission. To unpick that, let’s look at a typical museum mission statement. This one is from the Horniman Museum:

To use our worldwide collections and the Gardens to encourage a wider appreciation of the world, its peoples and their cultures, and its environments.

It is very easy for a production company to meet this aim, which means that the museum could easily give away a lot of money to these companies. But should they?

I would argue there are three things museums should be compensated for to pay for by film crews:

- Staff time

- Reduced productivity

- The intellectual property (IP) inherent in the objects and displays.

It’s very easy to put a price on staff time, relatively easy to put it on reduced productivity but very hard to put it on IP. But it’s the IP that most interests the film crews.

For the sake of argument, let’s say the staff and productivity costs of a day of filming are £500 – that could be two members of staff, costing £50 per hour for five hours, plus two school groups you didn’t book in, plus not being able to use the phone for a day.

That is how much the Museum is paying to facilitate a film crew, and doesn’t include the value of the IP.

If a film company were undertaking a project outside the museum that closely shared the museum’s objectives, and they asked you to donate that same £500, you would send them packing.

It really is the same thing.

Filming companies are commercial entities, who make money. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. Whatever you charge, they will make money off of your collection.

It’s not right that other people profit from your collection if the museum is left out of pocket.

Round 2: The marketing value?

Paolo in proposition

Jack is right to point out the costs of filming, but he hasn’t factored in the benefits that can be gained. This is possibly because it can be very difficult to put a value to the benefits in financial terms. If filming results in a positive message about your organisation, your staff and your collections – in line with your mission – then it can raise awareness about your organisation and demonstrate its value to potentially huge new audiences.

Of course, TV audience sizes will vary, but to get a sense of potential numbers reached, the BBC4 Secrets of Bones series, which used collections from all over the UK, had a weekly viewing figure of 494,000 between February 17th and 23rd 2014*. How much would you expect to spend on advertising to reach a similar audience? Keep in mind that the cost of a single 30 second advertising slot on one of the ITV channels averages £2,932 – a figure calculated from the 2015 ITV spot cost rates, which vary from £50 to £16,540 depending on the time of day and region.

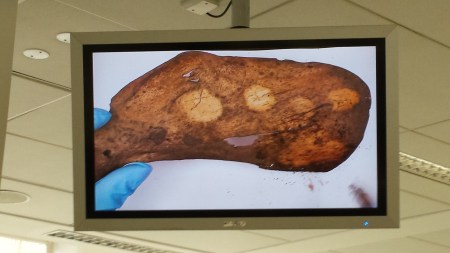

Another example of the potential audience reached by featuring in a TV programme is illustrated by the One Show broadcast on 4th June 2014 featuring an interview about cat anatomy in the Horniman Museum & Gardens Study Collections Centre. This had an audience of 3,610,000 viewers that week*. Put in perspective that means a specimen which had been off display for several decades was used to engage more than 4 times the number of people who visited the Horniman that same year (859,698 – taken from the Horniman annual report 2014-15), at a time when museums are being encouraged to make their stored collections more accessible. Compared to the amount of work required to supervise public tours of museum stores, prepare exhibitions, or administer loans, providing access for a film crew is remarkably cost effective for the potential engagement outcome.

When it comes to reporting, how might this kind of exposure be viewed by your trustees or the local councillors responsible for funding your service? For large organisations with high-profile activities it may not be so important, but for some smaller organisations with less exposure it may count for a lot more. Of course, I’m not saying that all filming in museums should be free of charge, but where the filming is sympathetic to what the organisation is trying to achieve, I think that the benefits can outweigh the costs.

Jack in opposition

It’s easy to see why this kind of argument is tempting – these are impressive numbers. It’s the same line the production companies use when trying to con you out of charging a fee.

However, I strongly believe that simply appearing in documentary as a venue has extraordinarily small impact on visitor numbers – or at least one that we haven’t been able to measure. Comments like “I saw you on the One Show” appear extremely infrequently in our visitor studies. I have never encountered a non-marketing production that generated any useful audience development. (But I do recognise that not all profile raising activity is about real life visitor figures.)

As much as they may try to tell you otherwise, I don’t believe that the simple “honour” of being seen on the BBC translates to strategic marketing. In all likelihood, the people that already know you are the ones that recognise you on TV, not new audiences.

Not only that, but it is essentially impossible to guarantee that mention of the museum’s (correct) name makes it into the final cut, and in my experience many companies won’t commit to doing so in the contract (for the logistical reason that they can’t keep track of all the people they might agree to include as editing progresses). This means you may think you’re getting good coverage, but then it ends up simply saying “I’m in this museum” on the final show, and you scream yourself hoarse at the TV (this has happened to us more than once, but fortunately we were paid so all was not lost).

To end, I can’t get away from the most important point of all:

Even if you do share their values, AND they agree to mention the museum’s name every thirty seconds, the production company is STILL willing to pay (whatever they tell you). Film crews ALWAYS have a locations budget, except perhaps News (please tell me if I’ve been sold a lie on that one!).

I feel bad pointing this out, but the Grant Museum also featured well in Secrets of Bones, and the One Show, with plenty of name credits. The thing is, they paid us.

The point is that you can meet your shared aim AND get paid. No brainer.

Thoughts from the floor:

Different organisations have different levels of demand for filming, so there are different degrees of cost and potential benefit. Bristol and the Grant Museum get lots of requests, so they become a major drain on resources and get plenty of exposure of their collections. Collections that aren’t situated near TV production companies get a lot less interest and may benefit far more from the exposure – and not charging may help encourage their use.

*Figures obtained from the BARB database [http://www.barb.co.uk/]

Jack Ashby is the Manager of the Grant Museum of Zoology

Paolo Viscardi is the Curator of the Grant Museum of Zoology, and that the time of the conference was the Deputy Keeper of Natural History at the Horniman Museum and Gardens.