Written by John-James Wilson (Lead Curator of Zoology, World Museum), Jude Piesse (Senior Lecturer in English Literature, LJMU) & Alyssa Grossman (Senior Lecturer in Communication and Media, University of Liverpool).

The interdisciplinary public engagement project ‘ENLivEN: Empire, Nature and Liverpool: Investigating and Engaging with Natural History’, is a collaboration between University of Liverpool, Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) and 14 city-wide partners. In this blog we bring together reflections from a workshop held at World Museum, Liverpool in October 2025, where we trialled approaches for the project with LJMU undergraduates. ENLivEN will develop further workshops on similarly evocative ‘catalyst’ specimens and objects held across participating institutions.

John-James Wilson (Lead Curator of Zoology, World Museum)

Spotted Green Pigeons are a species that became extinct at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

In 1793, Dr John Latham noticed two unusual taxidermized pigeons in private natural history collections in London. He described them as a new species that he called Spotted Green Pigeons. One of the specimens is now lost but the other was bought by the 13th Earl of Derby. In 1851, the 13th Earl of Derby left his specimen to the people of Liverpool in his will. Because the specimen is kept at World Museum, this specimen became known as the Liverpool Pigeon.

The Liverpool Pigeon is now the only known Spotted Green Pigeon specimen in existence. Uncertainty about the status and nearest relatives of Spotted Green Pigeons continued for over 200 years. DNA analysis in 2014 convinced scientists that Spotted Green Pigeons were a genuine, extinct species. Spotted Green Pigeons were only very distantly related to Feral Pigeons found in Liverpool and cities around the world.

We still don’t know where Spotted Green Pigeons lived before they became extinct. The Liverpool Pigeon was probably acquired by European travellers in the South Pacific, but we don’t know who brought the specimen to London. Some historians think Spotted Green Pigeons were the species known as ‘titi’ in Tahiti. Much about Spotted Green Pigeons remains a mystery, but the Liverpool Pigeon, like the Liver Bird, has become a Liverpool icon.

After being presented with this background information, students were invited to see the Liverpool Pigeon. They often asked for confirmation that the specimen was really the only surviving individual of the species and asked about how the specimen had been preserved. Like with most preserved animal specimens, emotional responses ranged from sadness to wonderment. Asked, ‘What was the most interesting, enjoyable, or memorable part of the workshop?’ nearly half the students (48%) said that having the chance to see the Liverpool Pigeon was their highlight. The Liverpool Pigeon is not on permanent display at World Museum, but a replica is displayed to tell the specimen’s story.

Jude Piesse (Senior Lecturer in English Literature, LJMU)

‘Mystery’ is one of the primary ingredients of story. When I first heard about the enigmatic Liverpool Pigeon, I felt we had the perfect hook with which to start one. The workshop we devised in response to the bird attempted to combine the mysterious with the tangible – as well as the local with the global – in creative and memorable ways.

As the British Empire’s ‘second city’, with a port of equivalent standing to Hamburg, Marseilles and even New York, Liverpool was an imperial hub for the global trade in animals and plants from the mid-eighteenth century onwards. This history has had lasting consequences, both in permanently shaping Liverpool’s landscapes and institutions, and through the city’s complicity in wider imperial violence and environmental degradation. How, our project asks, can we make such troubling legacies more visible, accessible and narratable, particularly for young Liverpudlians today?

Focusing on the Liverpool Pigeon and brief excerpts from Herman Melville’s 1853 novel Redburn – a fascinating attempt to imaginatively engage with Liverpool’s maritime and imperial identity that also contains one of the oldest printed versions of the city’s famous ‘Liver Bird’ myth – we delivered our workshop to 75 undergraduates. Through a combination of talks and activities on literary representations of the city, the Liverpool Pigeon, and the politics of taxonomy, students responded to difficult questions. How do local histories connect with histories of empire? To what extent do 200-year-old attitudes and behaviours predict contemporary environmental crises? And what are the stories, lost and found, within names?

Alyssa Grossman (Senior Lecturer in Communication and Media, University of Liverpool)

When we think about the contents of any contemporary museum, we need to consider how cultural institutions historically have mobilised their collections to promote colonial ideologies and value systems. By ordering specimens and objects according to positivistic categories of ‘primitive’, traditional’ and ‘savage’, Western museums could distinguish other cultures from their own, which they saw as more ‘advanced’, ‘modern’ and ‘civilised’. Through such classification practices, the power dynamics and cultural authority of the museum were reinforced.

Much of the key information that museums have is recorded the moment an object or specimen enters the collection. What often gets left out are more nuanced stories and perspectives from the communities where the objects or specimens originated. Objects are frequently taken out of context, mis-labelled. Museum records are brief, sometimes incorrect, with outdated or offensive terminology.

Rather than accepting ‘official’ museum taxonomies, we can challenge these histories and the absence of certain voices. There is a growing movement in the heritage sector towards co-creation and ‘mutualization’ of knowledge, where museums are starting to question their traditional role as gatekeepers of culture, and invite so-called non-experts into the processes of interpretation.

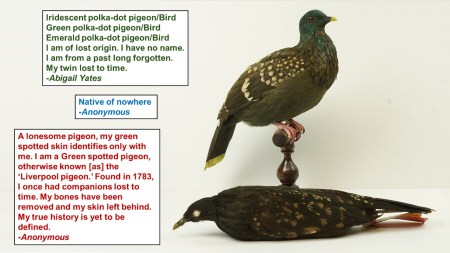

We asked students to come up with their own labels for the Liverpool Pigeon. Such publicly created tags are known as ‘folksonomies’, or folk-derived taxonomies. Unlike taxonomies, which are hierarchical and universalizing, folksonomies are bottom-up and informal. By inviting users’ own responses to encounters with objects and specimens, museums can begin to integrate other perspectives. Such practices can pose a radical challenge to established, authoritative colonial narratives about the past and present.

Student-written labels for the Liverpool Pigeon ranged from elegies for a lost bird to detailed descriptions that celebrate individuality.