Written by Leonie Sedman, Curator of Heritage & Collections Care, University of Liverpool.

Along with many other NatSCA members, I care for a mixed collection, meaning that one inevitably becomes something of a ‘Jack of all trades’ missing out on the academic satisfaction created by specialisation. As a curator who finds collections research to be the most satisfying part of my job, it can be frustrating when that research is often only possible on a ‘need-to-know’ basis – usually when a new display or exhibition is being planned, or when the specimens are to be used in teaching. Looking on the bright side though – this does provide glimmers of joy when the research produces something exciting!

In 2004 when I was first employed to manage the University of Liverpool’s Heritage Collections (medical & scientific museum collections built up through research or teaching), I retrieved a large proportion of the collections from attics and cellars where they languished because the objects and specimens were no longer actively used in teaching (this is now changing – but that would be a different blog). The Zoology Museum collection was one of these.

I was introduced to NatSCA by Roy Garner (then Head of Conservation at Manchester Museum) who was so generous with his time when I was grappling with the extent of my new responsibilities – then through NatSCA I discovered Simon Moore, and was very fortunate to be able to arrange for him to visit for a week to teach our team some of the skills we would need in order to maintain and improve the condition of the collection. As a very small team – every member of our embryonic department attended – including the Art Curator.

One of the first things I discovered about our zoology collection was its significance due to its origin – William Abbott Herdman established the teaching and research collection when he brought his own specimens with him from Edinburgh to take up his chair as Liverpool’s first Professor of Natural History in 1881. The collection still includes a number of specimens which either have Herdman’s name on the label, or which are obviously from the same era, but at some point in the early 20thC – many of the most interesting ones were rebottled and relabelled to be used as teaching specimens. This improved their aesthetic presentation but sometimes omitted valuable information from the original labels.

The lockdown period in 2020 disrupted my plans for a new display in collaboration with Earth & Ocean Science colleagues based on the contribution of the Challenger Expedition data to current climate change research – but it wasn’t all bad as it afforded some valuable time to do collections research. I was still at the beginning of my mission to learn as much as possible about the relevant subject matter, attempting to link it back to the one known Challenger specimen that was in our collection.

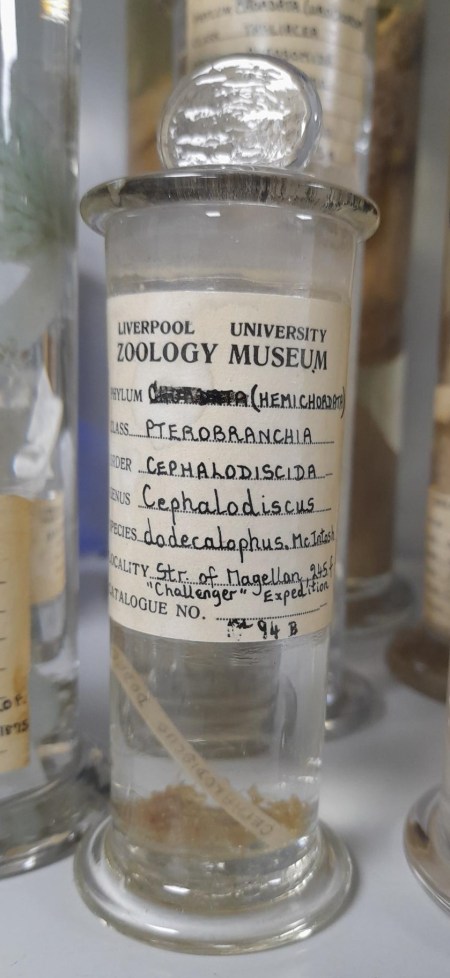

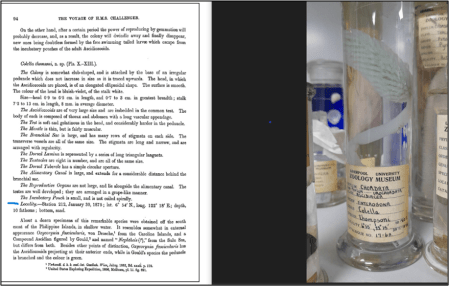

The labelled Challenger specimen – note that the reference to Challenger appears to be an afterthought – with screenshot of the paragraph describing its discovery. Image © Leonie Sedman, Victoria Gallery & Museum

I was keen to discover whether any of our other specimens were from the Expedition. Only one is labelled “Challenger”, but there was another which had been vexing me for some time. It was named “thompsoni” (extra ‘p’) and I knew that Wyville Thomson had been the chief scientist on Challenger (in Edinburgh, Herdman was his assistant), it had a date (30.01.1875, corresponding to Challenger) and coordinates on it – so I started by attempting to work out where the ship was on the relevant date. I asked one of the Marine Science professors to assist me in working out where exactly “6° 55, 22° 15,” might be (many of you will be able to spot my mistake in the photograph below). I scrutinised maps of the Challenger’s route, but it didn’t make any sense. Something more pressing came across my desk and this effort lapsed.

Fast forward to 2024, and another opportunity to concentrate on desk work presented itself – I broke my toe. Simultaneously, a colleague suggested that another of our specimens linked to Herdman should be included in a forthcoming publication – it was a type specimen named after Herdman. The first thing that happened when I started to research that specimen was my discovery of WoRMS – amazing! I was both overjoyed (a whole new world had opened up to me) and mortified (how had I missed this?). Within minutes I had discovered that our “type specimen” had been reattributed over 100 years ago (potentially assisting me in my efforts to work out when the specimens had been re-labelled) and it was not in fact a type specimen.

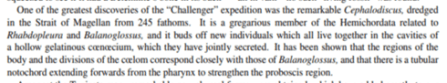

I was now of course moved to investigate my mystery specimen – as soon as I typed the name of the Colella into WoRMS – the word ‘Challenger’ appeared! Together with the relevant page numbers in the – now digitised online – Challenger Report. We have the Challenger Reports on the shelf in the store, but previously I had no idea where to start looking for the correct pages. Now, in the most ridiculously short time, I found not only the exact page where the discovery of our labelled specimen was recorded – but also the collection of the Colella. I had of course mis-read the coordinates – it was “122° 15” not “,22° 15”. The accepted name of the Colella is now Nephtheis fascicularis (Drasche, 1882). Words cannot express the joy and excitement that descended upon me – if I hadn’t had a broken toe I would have skipped around the room.

Colella on shelf, with screenshot of the relevant page of the Challenger publication. Image © Leonie Sedman, Victoria Gallery & Museum

However – despite this evidence I was painfully aware of the fact that I am not a marine biologist and was terrified that if I started crowing about my discovery – it was entirely possible that someone might pop up to tell me I was mistaken.

I turned to NatSCA for help and was given the contact details of Lauren Hughes at the NHM, who was able to confirm that I was correct – and who was incredibly generous and patient – feeding me information and publications to “help me become a marine biologist”. Lauren told me that both our Challenger specimens are syntypes, and that once we’ve photographed and listed the rest of our collection, Lauren and her colleagues will be able to investigate whether there are any more mislabelled treasures on our shelves. We are also planning to collaborate with the curators at World Museum Liverpool and Manchester Museum on the DiSSCo project. There is so much we will be able to learn from new information gleaned through the digitisation of our overlapping collections.

The beautiful Colella has since been published in the book that the original “type specimen” was going to be published in Collecting Stories: The cultural collections of the University of Liverpool published by Liverpool University Press – and it is also due to be included in a forthcoming multidisciplinary academic project.

Images: Lyndsay Roberts, © Victoria Gallery & Museum

It has now been 20 years since I first joined NatSCA, and the one constant linking everything above, has been the incredible support given by NatSCA members to each other. As a curator who manages collections which fall under a variety of different specialisms, NatSCA is the Subject Specialist Network which for me, stands out as an exceptionally supportive community where help and advice is generously and freely shared.

Pingback: NatSCA Digital Digest – December 2025 | NatSCA