Written by Dr Christina Thatcher, Lecturer in Creative Writing & Dr Lisa El Refaie, Reader in Language and Communication, Cardiff University.

With biodiversity declining at an alarming rate, we need to find ways of encouraging people to care about all endangered animal species, not just the ones with the most obvious appeal, such as pandas and polar bears, for example. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s ‘Red List of Threatened Species’, 27% of mammals are threatened with extinction, but so are 44% of reef corals, 41% of amphibians, 37% of sharks and rays, 21% of reptiles, and 12% of birds.

In 2023, we—Dr Christina Thatcher and Dr Lisa El Refaie from Cardiff University—met and discovered our shared interest in the expressive arts, metaphor, empathy and nature. We then designed a project which aimed to use the power of creativity to increase public awareness of, and empathy for, endangered animals, focusing on species that have few or no obvious human-like features. The project was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Impact Acceleration Account and ran from November 2023 until the autumn 2024, in collaboration with Natural History curators at the National Museum Cardiff.

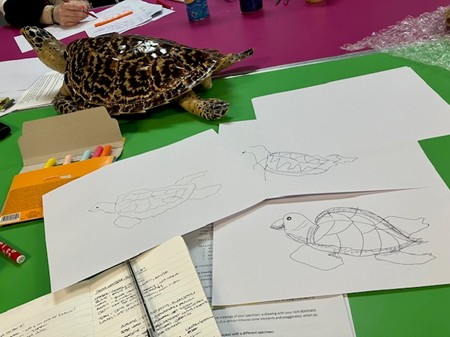

The curators selected specimens of endangered species from their collections, including a rhinoceros hornbill, a water vole, a white-clawed crayfish, a rainbow leaf beetle, a pink sea fan, and a scaly-foot gastropod. They also provided some key written information about these animals and their endangered status.

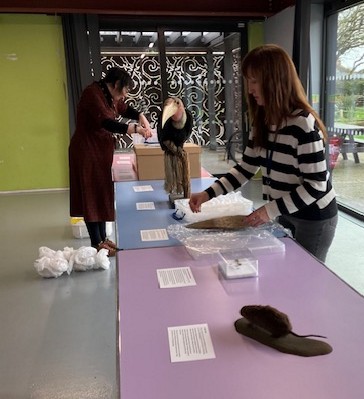

We ran three creative writing and drawing workshops in Cardiff, which were attended by 36 adults in total. The participants, many of whom had little or no experience in creative writing and/or drawing, were guided through a series of carefully structured activities designed to encourage the development of eco-empathy. The emphasis throughout was on expressing personal thoughts and emotions, rather than on the production of ‘good’ creative work.

After doing some quick ice breaker activities, participants were invited to observe one of the specimens carefully, draw them using different techniques (e.g., with their non-dominant hand, and without looking at their drawing), and then describe what they could see through writing.

The final stage of the first exercise involved combining the drawings and written words to create a detailed verbo-visual portrait of their chosen endangered animal (see the example of a tree pangolin below).

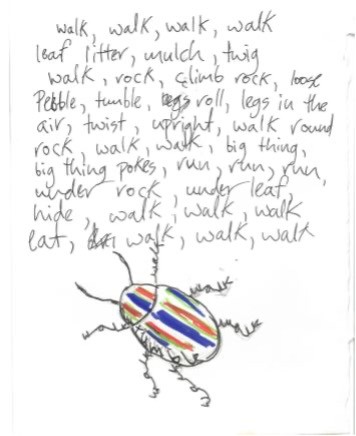

Another activity involved imagining what it would be like to be one of these creatures and, through writing, trying to capture its experience of seeing, hearing, smelling, feeling, tasting, and moving through the world. Combining this writing with their drawings, participants were inspired to compose verbo-visual pieces like the following one about the rainbow leaf beetle. These kind of anthropomophising activities encourage participants to draw on their imagination and embodied experience and, as we discovered in another project, ‘can lead to new connections being made between humans and the natural world, as well as inspiring individuals to engage with environmental issues in new ways’.

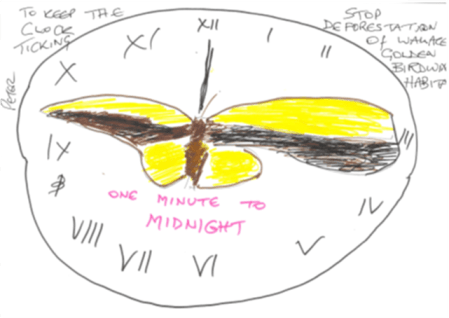

Our final activity drew on the power of metaphors. First, participants made a list of concrete objects they could see around them. They then wrote the name of one of the endangered animals and the word ‘is’, followed by three objects from their list, chosen at random. This process produced many unexpected metaphors, such as ‘the Rhinoceros Hornbill is a glass bottle’, which, in turn, triggered verbal and visual explorations of the similarities between them, giving people a new perspective on the plight of endangered animals. One participant drew the Wallace’s Golden Birdwing butterfly on top of a clock face, with the wings representing the hands of a clock moving closer to midnight and thus to a point of no return with respect to the destruction of precious habitats.

A Wallace’s Golden Birdwing merged with a clockface represents the increasing threat of the butterfly’s extinction

The creative activities, supplemented by written and oral information about individual species supplied by the curators, also sparked discussions about how to define the term ‘endangered’, why most people tend to be more interested in vertebrates than invertebrates, and what concrete steps we can take to protect and preserve the natural world.

In interviews a few weeks after the workshops, participants reported increased knowledge about endangered species, with one participant saying that ‘the creative aspect of reading and writing makes it more practical, visual, and it makes it more enticing and not so rigid and formal.’ Several people also described an increased willingness and ability to engage emotionally with particular animals by imagining what it might be like to be them: ‘that kind of connectivity you get. You wouldn’t walk down the road and think: what’s it like to be a vole? So, unless you do the actual activities, you’re never going to do that, are you?’

The workshops also fostered greater interest in the National Museum, as well as helping participants rebuild old relationships and forge new ones. Two participants became friends on Facebook after bonding over a shared interest in local swans, while another participant explained that, because of the workshop, he had reconnected with his stepchildren over their environmental activism and started to pick litter in his local community.

The collaboration has also influenced the educational and curatorial practices of the curators at the National Museum Cardiff, encouraging them to consider different educational methods of engaging audiences and new ways of approaching advocacy for endangered animals, for example, ‘by making connections between global and local conservation’.

A workshop toolkit with detailed instructions and guidance (in English and Welsh) is available to download free of charge by any individuals or organisations. Although access to specimens of endangered species is an advantage, the exercises can also be used with live animals (if they don’t move too much!), or else on the basis of photographs included in an Appendix to the toolkit.

We have received follow-on funding from the AHRC and are currently adapting the toolkit for use with primary school children in Wales, focusing on local bugs rather than endangered species.

If you are interested in learning more about this project, or would like advice on using the toolkit (for adults or, in the adapted form, for children), please contact Dr Christina Thatcher (thatcherc@cardiff.ac.uk).

Pingback: NatSCA Digital Digest – August 2025 | NatSCA