Written by Abbie Herdman, Curator of Invertebrates (Non-Insects), Natural History Museum, London.

The Natural History Museum, London (NHM) is currently undertaking one of the biggest collections moves in history, around 38 million specimens total (with 28 million moving off site). A diverse range of collections are expected to move to the new site in Reading including fossils, wet, dry, taxidermy and osteological specimens. This blog will focus on some examples and challenges faced when preparing the bryozoan collections to move.

Bryozoans are an astounding yet little known phylum of predominantly colonial aquatic invertebrate animals, found in both freshwater and marine ecosystems. Known as the ‘moss animals’, for a long time, they were thought to be plants which still confounds the record of this group in aquatic collections due to their growth patterns encrusting on rocks, as seaweed-like and sometimes as gelatinous blobs. There are bryozoan reefs which support diverse marine species, they are recognised bioindicators in aquatic habitats and are ‘blue carbon’ stores (Porter, J, S. et al., 2020).

The NHM Bryozoa collection is globally significant due to its age and size, from this legacy it continues to attract new material from current international researchers in taxonomy and ecology. There are many different preservation types in the collection from herbarium sheets to microscope slides, wet ethanol preserved or formalin fixed specimens, as well as a growing collection for DNA tissue analysis. All of which require varying levels of preparation and conservation.

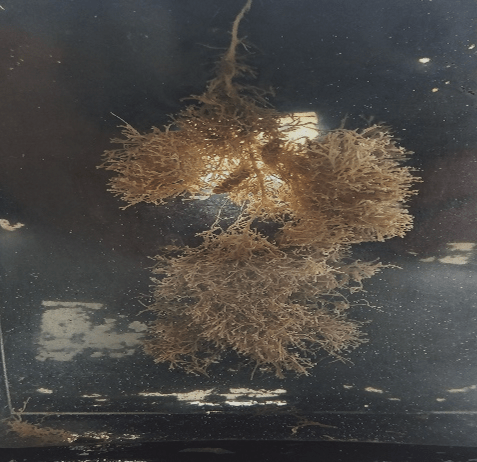

Bryozoan diversity. Photographs by Herdman (2024).

Dry Collections

Starting with the dry collections, this is currently where most work has begun on prepping the collection to move. The collections contain a variety of boxes and storage solutions, most of which are not up to current conservation standards due to factors such as acidic cardboard, broken boxes and the trickiest issue, somewhat unique to the Bryozoa collections, blue cotton wool.

Below is an example of the common ‘blue cotton wool’ issue. The wool is predominantly within the 1911/1912 Alfred Merle Norman collections. The Norman collection is a huge acquisition spread across various groups of invertebrates, with a large amount in Bryozoa. The biggest challenge here is picking tiny specimen fragments out of the cotton wool. Due to the colonial nature of bryozoans, every piece is essential to keep so this process is incredibly time consuming and sometimes is just not possible due to the nature of the specimen. The Norman boxes are also significant as the registration number is often written on the bottom, meaning this box can be used to reunite specimen data from the registers if the specimen ever became disassociated. Therefore, the decision has been made to keep the boxes but line the insides and wrap the specimens in acid-free tissue paper which has been Oddy tested.

Slide Collections

The slide collections are a work in progress currently, there are many unique slide types in Bryozoa and developing storage solutions is difficult. The diversity of the slide collection is vast, there are glass slides, wooden/plastic/cardboard cavity slides, Canada balsam slides, wax sections and then of course, SEM (Scanning Electron Microscope) stubs of all shapes and sizes. This means that sometimes standard slide cabinets and drawers are not suitable for keeping the collection stored well and in taxonomic order.

Some slides, usually of a standard size of about 1” by 3”, have been able to be put in boxes and added to the dry collection, so they are no longer recognised as a slide (and are no longer a problem!) This again also mitigates disassociation risks, particularly again with slides that do not have cover slips or where large specimens such as pebbles and shells are just bonded to a slide. So, this is the current solution of dealing with problem slides, however this then of course increases the footprint of the dry collection, so slides are very much in the trial-and-error stage.

Wet Collections

Across invertebrates, wet collection surveys have been carried out to identify commonly shared issues that can be addressed before the move. These include identifying ‘inadequate’ plastic lids, broken glassware, formalin crystals, mould, damaged labels and more. The NHM’s wet collections are amongst the oldest in the world meaning not only are the specimens are fragile, but some of the glassware is also at risk due to the age and in some cases it being hand-blown.

In the Bryozoa collections, the George Johnston collections are the oldest, having been accessioned in the 1840s. The jars are hand-blown so appear quite thin and wonky but have stood the test of time lasting over 150 years, but of course they need to last much longer so looking for the safest ways to transport them is essential. Lots of the Bryozoa collections contain glass vials within the glass jars, these are mainly used to house very small specimen samples or multiple samples within the same jar. A risk factor is currently under investigation for this method due to the potential risk of the vials and jars smashing and causing disassociation.

When moving spirit specimens, human health and safety is an important risk to consider due to the varying chemicals involved. For example, just across Bryozoa you can have ethanol, IMS (Industrial Methylated Spirit), Formalin, Rose Bengal, Bouin’s fluid and more concoctions. Appropriate PPE would be used, and other risk assessments will be developed.

The Herbarium

The Bryozoa herbarium is relatively small but very historically significant, it does contain type material such as the type of Alcyonidium diaphanum (Hudson, 1778), but also a trove of curator’s and collector’s handwriting and notes spanning over centuries in some cases. There are some challenges at present, not all the herbarium specimens are housed or preserved as current guidelines recommend (Bromberg, 2020), so many would need some level of conservation. There are loose specimens and labels within some of the specimen folders which of course would need to be reassociated before the move. Once the specimens have been conserved, it would be ideal to digitise them using established methods at the NHM (Lohonya et al., 2022), for digital loan purposes to prevent excessive handling with the very historic material.

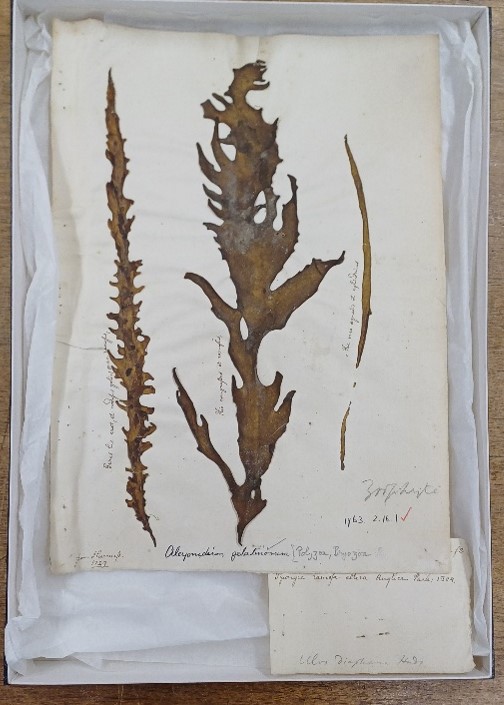

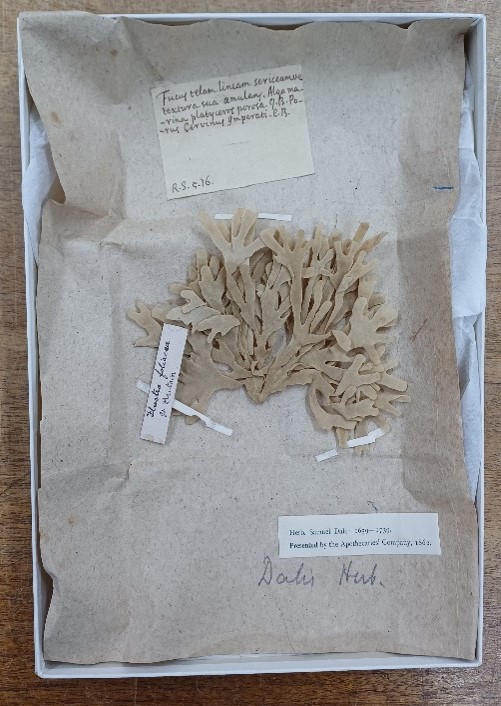

Animals as plants: Two of the oldest specimens in the collection. On the left is the type specimen of Alcyonidium diaphanum (Hudson, 1778) and a specimen of Flustra foliacea (Linnaeus, 1758) from botanist, Samuel Dale which dates the specimen from between 1659-1739. Photographs by Herdman (2024).

Work is continuing across the museum to prepare the collections to move, find out more here: https://www.nhm.ac.uk/about-us/science-centre.html

References:

Bromberg, L. (2020) ‘Best practices for the conservation and preservation of herbaria’, The iJournal: Graduate Student Journal of the Faculty of Information, 6(1), pp. 1–13. doi:10.33137/ijournal.v6i1.35263.

Lohonya, K. et al. (2022) ‘Digitisation of the Natural History Museum’s collection of Dalbergia, Pterocarpus and the subtribe phaseolinae (fabaceae, Faboideae)’, Biodiversity Data Journal, 10. doi:10.3897/bdj.10.e94939.

Porter, J, S. et al. (2020) ‘Blue carbon audit of Orkney waters’, Scottish Marine and Freshwater Science, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.7489/12262-1

Pingback: NatSCA Digital Digest – September 2024 | NatSCA