Written by George Seddon-Roberts, PhD Student, John Innes Centre, work completed whilst on placement as a Curatorial Intern at Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales.

When accessing an entomology collection, there are a few things that a researcher can expect to find. Each specimen should be pinned with labels describing its species and information about where it was collected – two valuable pieces of information which can help researchers to trace the specimen’s origin geographically and in time. Knowing where and when a specimen was collected can help researchers better understand the historical landscape and ecology and make predictions into the future. However, when collections receive specimens from private collectors, this standard of labelling might not be met. As part of a 3-month internship at Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales, I aimed to transform one such collection.

The collection in context

John Henry Salter (1862-1942) was an academic and naturalist, who spent much of his life as a lecturer at University College of Wales in Aberystwyth, where he would later be appointed as the first Professor of Botany. Outside of academia, Salter was a prolific collector of insects across several groups, most notably including coleoptera (beetles) and lepidoptera (butterflies and moths). Salter’s collection contains specimens from across Wales, as well as England, Tenerife and south-east France; regions where he spent time during his retirement. The specimens, which amount to over 15,000 individuals, were meticulously recorded in field logs by Salter, which were also donated to the museum with the collection.

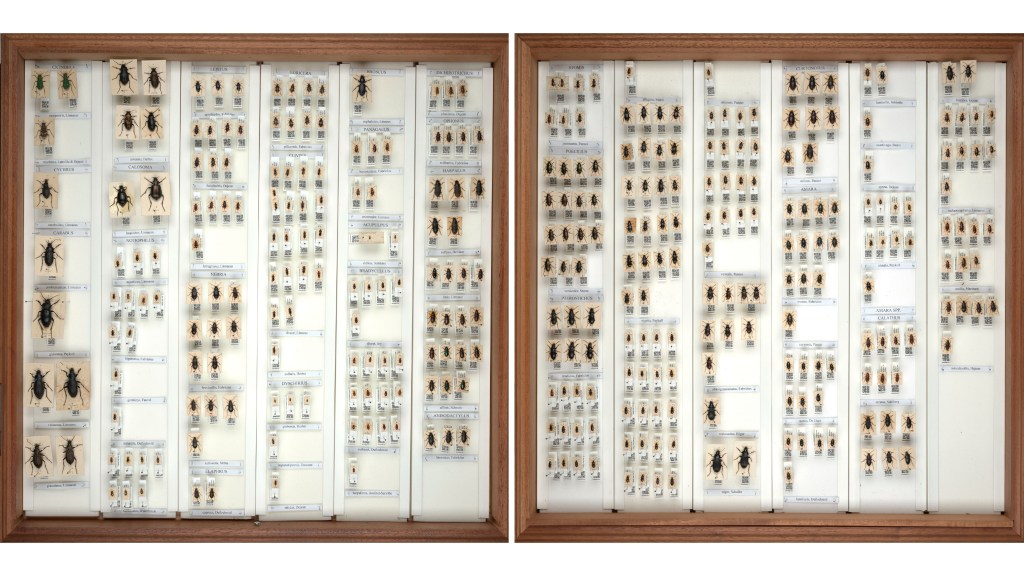

My work at Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales focused on a drawer of Carabidae (ground beetles) collected by Salter in Ceredigion between 1923 and 1942, which contained around 300 card mounted specimens without locality or species identification labels. Each card contained only the specimen and a small, handwritten number pertaining to the relevant entry in one of Salter’s field logs, which held the information about the location and date of specimen collection. The goal for my time at the museum was to make the specimens in the drawer more useful to those accessing the collection in the future, by giving them detailed labels, and uploading their information to the relevant collection databases.

Pinning down localities

Typically, locality labels contain various information, including the point locality where the specimen was collected. In the Salter collection’s case, however, the only locality information we had was based on localities as they appeared in Salter’s field logs (the verbatim locality), which were often relatively non-specific, and likely meant much more to the collector himself than they do to today’s researchers. As such, I needed to assign more appropriate localities, which included a standard ordinance survey grid reference, and geographical co-ordinates (point localities). This required me to track down each location in Salter’s field log – a task more easily said than done, given the significantly cursive nature of Salter’s handwriting – and then use a variety of resources to determine the point locality that the verbatim locality may refer to.

Verifying species determinations

After fleshing out the information which would populate the locality label, I needed to verify the species identifications. Given the ever-shifting taxonomic landscape of the group, it was possible – and in fact highly likely – that some specimens which had been identified as one species, may now be understood to be a different species. As such, using the most up to date identification keys for the Carabidae, I was able to determine the species of most specimens, save for those that were significantly damaged, or where identification relied on features that were inaccessible (due to the nature of card mounting).

Curation and digitisation of specimens

Now that the locality and species determination labels were ready, as a conservation measure, I replaced the existing pins on the mounts with stainless steel pins, which will resist corrosion, an issue we were seeing in the original pins. I was able to image each specimen – alongside its locality and species identification labels (as well as labels that acted as identifiers for each specimen’s place in the database and image library) – then upload each image to the museum’s natural sciences image library. These uploaded images, together with the collection database, leave a visual and written record of the specimen as it exists after my project’s conclusion.

Project conclusions

Reflecting on my project, I have been able to transform the drawer of unlabelled specimens into a curated and digitised collection of specimens that are accessible for the future, with a digital footprint which may last much longer than the specimens themselves. Along the way, I have learned an array of transferable skills, including aspects of curation, georeferencing and digitisation. I have also been able to carry the workflow of curating a collection from beginning to end, experience which will be invaluable in my career going forward. However, and perhaps most importantly, I have made connections with numerous colleagues, whose wisdom and guidance have been essential in the completion of the project.

Pingback: NatSCA Digital Digest – September 2024 | NatSCA