Written by Pauline Rutter – Independent Archival Artist, Community and Organisation Poet.

These words look out from the page with eyes I have borrowed. Eyes not shaped for vision through the specific disciplinary scientific lens. Eyes that strain to see beyond past centuries of debate on what, of all origins, is knowable and what is not. With these original eyes, would ways of seeing allow the light to travel outwards resisting funnelled perspectives and interpretations descended from imperialistic systems of Enlightenment science, colonial ideologies and narratives? In this context my eyes had opened up unevolved or re-evolved with lepidopteran vision, though not removed from all that had been taught to be seen. New eyes with sight of intensified colour that amplified nature’s interconnecting patterns, only visible outside the spectrum of the everyday, the expected, the predetermined.

What use is butterfly sight that transforms configured objects and living matter with or without full binominal species names, into fragments like those of the intertwined and metamorphosed elements in ritualistic rapture spreading out across a Wangechi Mutu collage?

Be still a moment eyes. Your attentive audience is attuned to the practical work behind the scenes of Natural Sciences collections and of engaging projects. But deny what this sight has shown you at your peril and instead begin.

- Image 1. Inside the Booth Museum Brighton P. Rutter (2024).

- Image 2. Making a Difference: NatSCA Conference and AGM 2025. (P.Rutter, 2025)

Begin

Begin with a title, ‘A restitutive commitment to community and to the natural environment through storying with natural history collections.’ Ask if there’s more to offer than the summary of a National Trust, Changing Chalk enquiry, that had drawn me out of the Booth Museum ‘From Collections to Connections’ via herbariums, cabinets and cases, to evolved upright walking on the Sussex South Downs.

- Ramble the chalk grassland hills with families of many diaspora’s

- Enter into the histories of settlement, of grazing, of climate, geology and enduring colonisation

- Ask if a child entomologist’s renaming of Lycaena phlaeas, Small Copper butterfly, would make her any less beautiful?

What else might this audience want to know? That ‘From Collections to Connections’ was designed in 2024 as an archival art, natural history, environment and community connecting initiative? That I came to this work with Black feminist sistas and elders steering me through the almost invisible intergenerational, intersections of Natural Science collections historiography. That my butterfly vision drew me towards the stories surfacing from across the former colonies and that insisted I settle with them for a while to sample the knowledges within their sweet, restorative nectar.

Was there time to explain the numbers?

- 7 drawers of specimens viewed from among 400,000 Lepidoptera, gradually finding a digitised home within the Booth Museum’s Mimsy database. Astounding!

- 13 million butterflies in London’s Natural History Museum collections. Unimaginable!

- 1.5 billion specimens of all types with their origins intricately linked with global cultures, held within Europe’s history centres. Unfathomable!

Was the language of the Savoy Report of 2018, too open with the wounds of unrequited restitution, to have any place in a poetic reflection on the collections inspired words and wanderings across the South Downs? With lepidopteran vision in full circle, you can’t help but see from left to right, above, below, behind and what’s coming up ahead.

Seek

To turn a corner in the Booth Museum loft, is to take an anthropoidal research trip several times around the world. What rests on top shelves and against walls, becomes as fascinating as the treasures in a 1970’s office cupboard or an Edwardian cabinet full of specimens from every continent and with no record of how they were collected. Or with culturally native names overwritten with those sometimes too offensive to repeat. The finding of each searched for item is always the buried treasure at the end of the hunt, even if discovery becomes another wound to heal.

Day Two: Cabinet 225, Harlington collection, 1889, Hippocrepis comosa, Horseshoe Vetch. A satisfyingly unspectacular locating of an ecologically significant perennial legume. Flat, dried fragments in a daybook of 135 years ago. A starting place for a story of a late Spring walk on the Downs. Of a stroll up to the chalk turf, south-facing slopes where rabbits keep the sward short. Of the brilliance that is Horseshoe Vetch, offering up a lavish patch of green foliage and opulent yellow blooms. Then to ask, what context has an illustration where Chalkhill Blues alone sip the acid nectar from the flower? Where the flower has struggled through a Spring so warm, unsettled and wet. Where below ground silent microorganisms fix nitrogen to roots in a symbiotic dance without which nothing would remain.

- Image 3. Booth Museum Brighton, Harlington collection, 1889, Hippocrepis Comosa, Horseshoe Vetch. (P. Rutter, 2024).

- Image 4. Illustration of Horseshoe Vetch with Chalkhill Blue butterflies. (@Honeyteacakez, 2024)

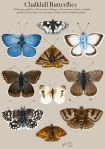

- Image 5. ‘From Collections to Connections.’ Original illustration of chalk grassland butterflies found on the South Downs. (@Honeyteacakez, 2024)

Discover

What of the other histories that set me on this path from collections to deep connections? One story from the Das & Lowe (2018) lead, enticed me to Hintze Hall of London’s Natural History Museum. Follow, follow, follow the terracotta monkeys up to the refurbished second floor in search of a hand decorated ceiling panel of ‘Quassia amara.’ Follow on to the unaccredited, now accredited, decontextualised now contextualised life story of Graman Kwasimukambe (1692 – 1787). Kwasimukambe, Ghanese born, once plantation-enslaved African. One among 220,000 captives to the Dutch colonists of Suriname. Kwasimukambe, honoured in 1762 by Carl Linnaeus who gave his name to the plant Quassia amara. Though with its native name obscured, also called amargo, bitter-ash, bitterwood, or hombre grande. Kwasimukambe, revered for using the healing properties of this bitter plant’s leaves and heartwood to relieve fever, pain and inflammation of all who sought him out. Kwasimukambe, traitor to the Saramaka maroons, who took his right ear while he played the part of a Dutch scout. Caught up in the Saramaka hundred-year war, fought ferociously until their freedom from the Dutch Crown was won with a treaty signed. An unsubstantiated promise for territorial rights in the very year that Quassia amara was given the name of our Kwasimukambe.

- Image 6. Interactive Ceiling Panel Display 2nd Floor Natural History Museum London. P. Rutter (2025)

- Image 7. Quassia amara ceiling panel among 162 of the Hintze Hall decorated ceiling, Natural History Museum London. (P Rutter, 2025)

Seeing with their Eyes

With this lepidopteran vision, I gazed upon a thousand South Downs Chalkhill Blues in rows within filled trays of pinned collections. Far fewer rising up to the call of the sun across the grasslands where sheep and people roam. Do we share a vision of restoration, repatriation and restitution? Of seeking out long-lasting commitments to equity, to community and to the natural environment? Of vast embodied perspectives that welcome our responses to the small and trampled stories these collections might well tell. Could the words of a poem take flight from the page to dislodge the blinkers just enough to let you see anew?

Their eyes through my eyes.

Seeing in irresistible patterns

Of Grizzled Skipper ultraviolet vision.

That fuses unaccredited collectors real names

To the unravelling of empire’s legacies.

With histories more vivid than Red Fescue

Bedazzling the summer Marbled Whites.

Eyes wide open.

With their multiple receptors

Catching more than the indigo purples of Round-Headed Rampion.

Telling more of what lies beneath

A revised collections label

Than the whispered promise of provenance acknowledged.

Of honest stories and injustices revealed.

Of nonperformative statements

Drawing in none of us

Who seek such visual brilliance

As could excite these expansive fields.

Like the Springtime yellow across the Downs

That Horseshoe Vetch lights up.

So, in full view, the decolonial knowledge

Becomes the decolonial acts.

With an honourable promise

To spread their outstretched wings

Of funds and resources, much wider.

As broad and sure as those of migrant Painted Ladies

Travelling, in succession every Spring

Some ten thousand miles from Saharan Africa

To these wind-swept shores.

Bringing with them irresistible pre-colonial truths

That would dapple the chalk grassland fragments

Like the whispered lilac-blue

Of summer Field Scabious flowerheads

Purposely in bloom.

Take a breath and one breath more

As all this melanated speculation stills.

To wonder if to liberate our vision

To reveal, redress, revive and to re-view

Through the breadth of compound sight

Such current and historical imbalances

As would keep us all huddling on just the scientific spot.

To find the fullness of this vista

Opens space for many more to enter into view

Bringing with them limitless knowing and creation

A free and liberating clarity

That is seeing with their eyes.

- Image 8. Chalkhill Blue, New Timber Hill. (P. Rutter, 2025)

- Image 9. Painted Lady c/o Butterfly Conservation

- Image 10. ‘From Collections to Connections’ June walk on Mill Hill West Sussex. (P. Rutter, 2024)

Some References and Resources

Das, S. & Lowe, M. (2018). Nature Read in Black and White: decolonial approaches to

interpreting natural history collections. Journal of Natural Science Collections, Volume 6, 4 ‐ 14.

Jennings, G. and Jones-Rizzi, J. (2017). Museums, white privilege and diversity: A systemic perspective. Dimensions, pp.63-74.

Tanner, R. L., Wilsterman, K. (2025). Beyond diversity initiatives: Building a community of care in scientific societies, BioScience, Volume 75, Issue 8, Pages 659–663.

Sarr F, Savoy B. (2018). The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics. Ministère de la culture.

Sebuliba, S., Wesche, K., Willi, E., Xylander, R. (2021). Ready for Restitution? Meeting Challenges of Colonial Legacies in Africa’s Collections, BioScience, Volume 71, Issue 4, Pages 322–324.

Butterfly Conservation: Research, figures and images

Decolonising Brighton & Hove Museums – More Questions than Answers by: Simone La Corbinière

Decolonising the Natural History Collection at the Booth by: Lee Ismail

Decontextualise to Decolonise Brighton Museums

From Collections to Connections: Pauline Rutter National Trust Changing Chalk 2024

Thunderstruck: Wangechi Mutu (Kenyan, b. 1972), Untitled, 2004. Mixed media on paper

Pingback: NatSCA Digital Digest – October 2025 | NatSCA