Written by Jazmine Miles Long – Taxidermist & Bethany Palumbo – Head of Conservation, Natural History Museum Denmark.

Taxidermy collections are crucial for our understanding of biodiversity, evolution, population genetics and climate change. They form a large part of natural science collections and their long-term preservation is essential. Historically, taxidermy was created using natural, durable materials such as wood, plant fibres, wax, clay and glass with examples dating back to the 16th century. However, over the past 50 years, taxidermists have increasingly adopted synthetic and plastic-based materials due to their ease of application, lower cost, and effectiveness in creating realistic specimens. One such example is polyurethane, a very widely used material to build the form that goes under the taxidermy skin. Although polyurethane has been extensively tested (albeit not specifically for taxidermy), it has already been shown to be unstable and unsuitable for long-term use. Awareness of stable, durable materials is not widespread within the taxidermy community. As a result, many modern museum taxidermy pieces are made with untested and potentially unstable materials.

This research began in 2021 with two primary aims: first, to investigate the composition and deterioration of modern taxidermy materials; and second, to encourage the taxidermy and museum communities to consider longevity and best practice when creating or acquiring taxidermy.

Ultimately, this research aims to provide guidance on the suitability of certain materials for specific purposes, in this case museum taxidermy. For example, is the specimen of scientific importance, or is it intended for long-term display or handling?

Here, we present an update on the research to date, including preliminary Oddy test results and future plans for this ongoing work. Although a selection of taxidermy materials were Oddy tested in 2021, the authors decided to redo the Oddy test. The reasons for this were:

- Lack of complete results from the 2021 testing.

- Inconsistencies with external testing and internal testing methods.

- Additions to materials list due to recent changes in commonly used materials.

1. Methods applied: the ‘Oddy’ test.

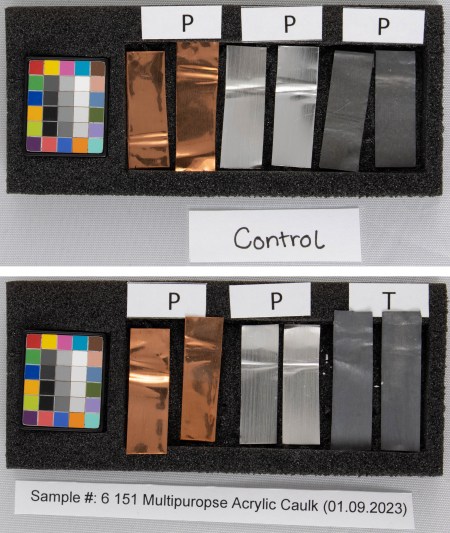

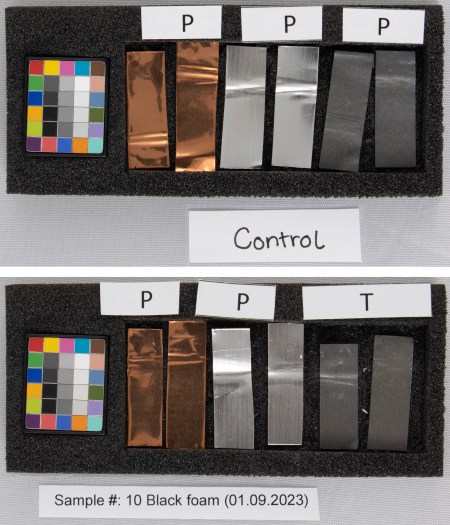

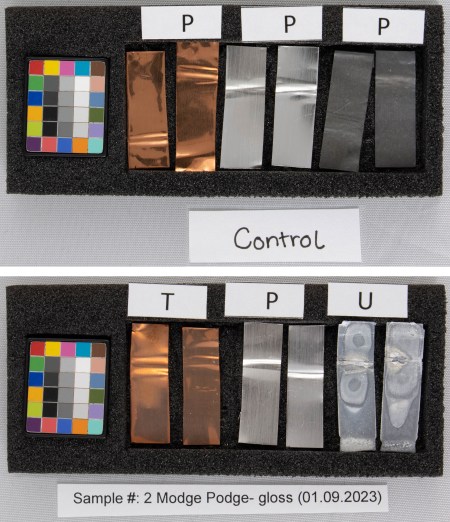

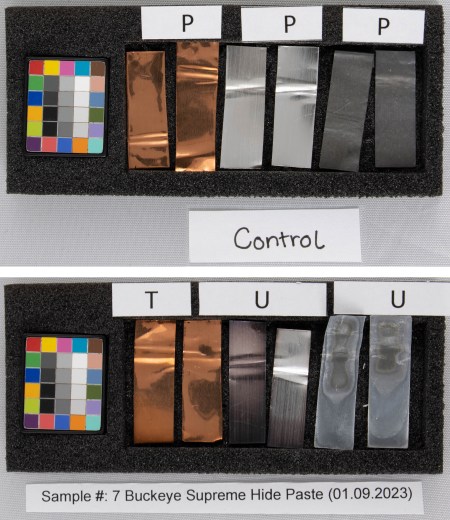

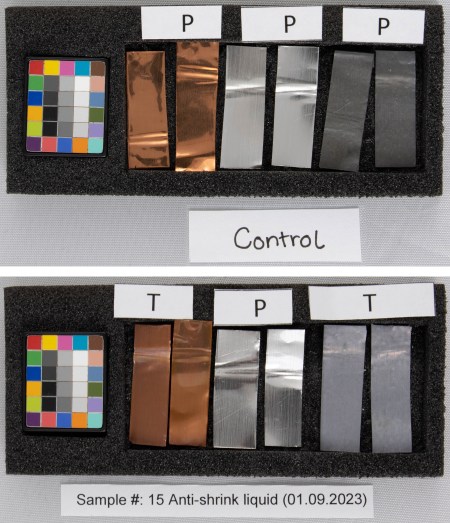

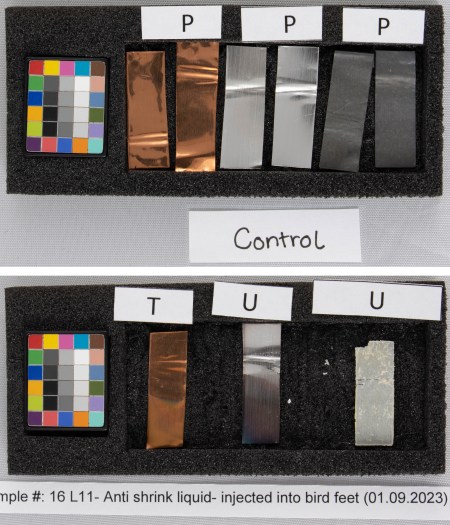

The Oddy test is a procedure used to evaluate the suitability of materials for use around museum objects. It involves exposing metal coupons (silver, copper, and lead) to the material in a controlled, accelerated environment for 28 days. Any signs of corrosion on the coupons indicate that the material releases harmful gases that could damage objects over time.

Tested materials are grouped into 3 categories:

- ‘Pass’ (P): No visible corrosion on the coupons. Material can be used permanently.

- ‘Temporary’ (T): Slight visible corrosion (darkening or tarnishing to the coupon). The material is safe for use near but not in contact with art for up to six months.

- ‘Unsuitable’ (U): Severe corrosion, tarnishing and crystal formation. Not to be used.

One of the main issues with the Oddy test is the subjectivity involved in interpreting the results, as it relies primarily on visual assessment. It is also important to remember that the test measures the reaction of a metal coupon to another material in an extreme environment, under high humidity and high temperature. Therefore, it does not indicate how a material will react in a ‘room temperature’ environment. Nevertheless, the Oddy test serves as a good indicator of a material’s suitability for use around museum objects or, in this case, for use in taxidermy manufacture.

The Oddy tests 2023

The method used was the Oddy Test Protocol 2017 from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET). This was familiar to the authors and has been continuously refined and replicated many times over the last 15 years (J. Bakker-Arkema, R. King & E. Breitung, 2023). According to the American Institute for Conservation (AIC), corrosion observed on the coupons indicates exposure to various compounds; specifically, silver detects reduced sulphur compounds, lead detects organic acids, aldehydes, and acidic gases, and copper detects chlorides, oxides, and sulphur compounds.

Using the MET 2017 testing protocol, the rating of the coupons (pass, temporary or fail) are defined as follows:

Permanent (P) rating: The material tested may be used indefinitely in the presence of objects.

i. Coupons look similar to the controls.

Temporary (T) rating: The material is safe for use near but not in contact with objects for up to six months.

i. Copper: slight reddening, yellowing, or rainbow-like colour change, formation of up to 20 black spots

ii. Silver: white splotches, slight yellowing, or purpling

iii. Lead: darkening, yellow/olive tarnish, haze from slight crystal formation over the entire coupon, or heavier crystal formation at the interface with the stopper.

Unsuitable (U) rating: the material should not be used in contact with or near objects and another material should be found.

i. Copper: severe blackening or severe reddening or matte-textured surface.

ii. Silver: severe colour change to dark purple, yellow, or black; or a uniform white film.

iii. Lead: white fluffy crystal formation, corrosion that has physically destroyed the coupon.

The results

For a material to fail the Oddy test, there must be significant corrosion on 1 of the 3 coupons. The main outcome from this round of testing is that none of the materials passed the Oddy test for permanent use. The majority received a temporary rating and a small number failed outright. The full results will soon be published online and publicly available, with the link added to this blog post in the near future.

Popular materials that received a temporary rating include:

Acrylic caulk – A very popular material used to create structure, strength and detail. It is injected/inserted between the skin and the sculpted form after the skin has been mounted but before the skin has dried and is used to fix the skin into place.

The four high-density foams (including polyurethane and polystyrene) used to mould or carve mannequins/forms.

Popular materials that failed the test include:

Mod Podge – Used to add details around the eyes, mouth and nose. Both the matt and gloss version of this material failed the oddy test with heavy white corrosion on the lead coupon, indicating the release of acidic, organic gasses.

Buckeye Hide Paste – This material is used to adhere the tanned skin to the mannequin. The paste corroded both the silver and lead coupons, showing the release of sulphuric compounds.

The L11 birdfoot injection aims to reduce shrinkage of bird feet as they dry. It received a temporary rating when tested on its own. However, once injected into an actual bird foot, it failed the Oddy test, corroding both the silver and lead coupons.

Conclusions and Future Aims

This testing round has revealed interesting outcomes. Purpose-made materials such as the Buck-Eye hide paste demonstrated their instability while industrial-grade hard foams and acrylic caulk are, on first assessment, more stable than expected.

While long-term stability isn’t the priority for all taxidermists, having a better awareness of materials and their potential reactivity allows taxidermy artists and museum clients, for whom longevity is important, to consider their choices when applying these materials. Temporary materials are often used in art conservation due to limited alternatives, so museums may decide a temporary material is sufficient for taxidermy construction. It should also be considered that a tanned skin itself can be acidic with a freshly tanned skin at around pH 4 – 5.5, the pH of the leather depending on the chemicals and processes used in the preparation and tanning process.

The authors wish to continue this research, but the scope is large with many materials to consider. To ensure the next research stage is relevant and useful for the field, we would like your help deciding where to focus next. Please help us by filling out this short questionnaire and share it to other taxidermists and museum professionals – https://forms.gle/LEogM5e51nJD5uUFA

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sarah Burhouse for providing the material samples and also Devon Lee, Nicole Feldman and Mikkel Bartholdy for their assistance undertaking and assessing the 2023 Oddy test at the Natural History Museum Denmark (NHMD).

Citations

- J. Bakker-Arkema, R. King & E. Breitung (2023) Benchmarking the Oddy Test: Development of Damage Thresholds and a New Tool for Standardizing Material Tests for Cultural Heritage Institutions, https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/benchmarking-oddy-test

- American Institute for Conservation (AIC) https://www.conservation-wiki.com/wiki/Oddy_Test

- Marion Kite, Roy Thomson (2006) Conservation of Leather and related Materials. Routledge.

- J. Churchill (1987) The Complete Book of Tanning Skins and Furs. StackPole Books.

- Matt Richards. Traditional Tanners, Fur on bark tanning course. https://braintan.com/product/barktanclass/

- Leather Conservation Center https://leatherconservation.org/. Leather conservation course hosted by West Dean (2024). Taught by Mike Redwood, Rosie Bolton and Arianne Panton.

Pingback: NatSCA Digital Digest – May 2025 | NatSCA

Pingback: Bark Tanning Skins into Leather for Taxidermy – A Sustainable, Natural and Non-harmful Alternative to Commercial Tanning Products? | NatSCA

Pingback: Top NatSCA Blogs of 2025 | NatSCA