Written by Jack Ashby, Assistant Director of the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge.

Pat Morris is the authority on the history of British taxidermy, and there is arguably no-one better to write an exploration of the specific context of taxidermy collected for and displayed in private country houses. Although their materiality is identical, by their nature, these collections are often conceptually very different – the antithesis, even – to those in public museum. These differences are not the focus of the book, nonetheless this perspective offers great potential to help us consider more roundly the story of taxidermy and those that made and collected it.

The similarities museum and country house collections do share include their origin-stories, and of course the practicalities of preserving specimens. Like museums, these private collections trace their histories back to cabinets of curiosities. Preservability was fundamental to what could be kept, and Morris begins by explaining that early cabinets of curiosities in country houses were mainly items that required no preservation – dry materials like shells and bone. The only skins that were widely kept were those that could be simply dried without being prone to insect attack, which is why durable specimens like taxidermy crocodiles, hollowed-out armadillos and inflated pufferfish were commonplace in these early collections, rather than the birds and mammals which later became the norm.

Morris charts early attempts at taxidermic preservation, leading to the development of arsenic soap in the late 1700s, which enabled the spread of taxidermy in country houses – as in museums – from the early nineteenth century. The book runs through the different techniques developed for the taxidermy of different animals – and the big names in the business of taxidermy – including fascinating details that most viewers wouldn’t necessarily think about, such as how they dealt with animals’ eyelids, lips and ears. Morris offers insightful details, such as that fish mounts were typically varnished to given them a “wet look”, so that we imagine their entire diorama setting to be an underwater scene, even though fish only look wet when they are out of water; he also queries the inclusion of the flowers of aquatic plants within these dioramas, when the species depicted bloom above the water.

Taxidermy and the Country House gives accounts of the practices of many of the taxidermy firms that also supplied museums. A big part (possibly the biggest, given the size of the market) of their trade was in hunting trophies for country homes, including by Gerrard, Ward, Spicer and Van Ingen & Van Ingen. Indeed the latter, a British firm operating out of Mysore, became the largest taxidermy organisation in the world – in 100 years of trading from the 1890s, Van Ingen & Van Ingen handled at least 20,000 tigers and 23,000 leopards. This was a big business for Britons serving imperial functions in India, and the wealthy on hunting safaris in East Africa.

Morris lists the primary motivations of the big collectors, and points out that some of the most significant country house collections served no other purpose than that the owner enjoyed “having them around as part of his personal environment”. Unlike those that were used by the collector for independent scientific study, or as a tool for social networking, these motives appear purely acquisitional. Elsewhere, the natural historical value of these collections were central, in that they displayed the species of birds that could be found on the estate or nearby, as well as prize bulls they’d reared. Others commemorated particularly memorable visitors – through taxidermy game birds shot by royalty. Both tactics had social functions – to show of the richness of their land and the significance of their networks.

Hunting trophies, too, are a major feature, as are the changes in the public’s taste for such objects. Readers will be left in no doubt of Morris’ view of recent shifts in how hunting trophies are appreciated (or not) by visitors to country houses, and he spares no emotion in regularly bemoaning their relegation to the stores, or worse – their unfortunate destruction. It’s something of an exposed nerve for someone who clearly cares so deeply about historic taxidermy.

Many of the collections in the book are the legacies of individuals who spent their lives amassing vast taxidermy collections as personal passion projects. This is a major difference between the motivations of museums and country houses – museums collect for perpetuity, but that is not the driver of individual collectors. Once they die, the people they leave behind inherit the responsibility of caring for vast collections of unstable specimens easily prone to deterioration without expert (and expensive) care – as we in museums all know. Garry Marvin – an English anthropologist who focuses on cultures of hunting – suggests that hunting trophies never have more meaning than when they are owned by the person that shot them, as a re-liveable symbol of the hunter’s “relationship” with the hunt (Marvin, 2011). I think Morris would agree, but nonetheless he doesn’t seem to have much sympathy for those descendants who don’t feel the same way about wanting to live in homes surrounded by their deceased relatives’ hunting spoils.

Little space is given to the societal contexts of many of the characters Morris mentions, for example any links to legacies of enslavement or exploitation, and the opportunities taxidermy collected under these circumstances offers for exploring such narratives today. Indeed, I was left with an unfortunate taste in my mouth from the significant push-back that Morris delivered against exploring these particular social histories. He feels that any such investigations into colonialism is “overlooking the benefits it conferred”, which is surely not consistent with a desire to explore these collections’ true and complete stories. I would suggest to those who feel that researching colonial legacies as something of a threat, that this misses that it is an additive process, not a destructive one.

Nonetheless the history Taxidermy and the Country House offers is a valuable one to anyone interested in such collections, and particularly those in museums, for several reasons. Museums became the repositories for many of these collections as they were sold by their owners or those that inherited them; the same taxidermist were supplying both markets, so the book offers useful insights into how museum collections were amassed; and it offers real value in considering the differences between the practices and motivations behind the two modes of collecting.

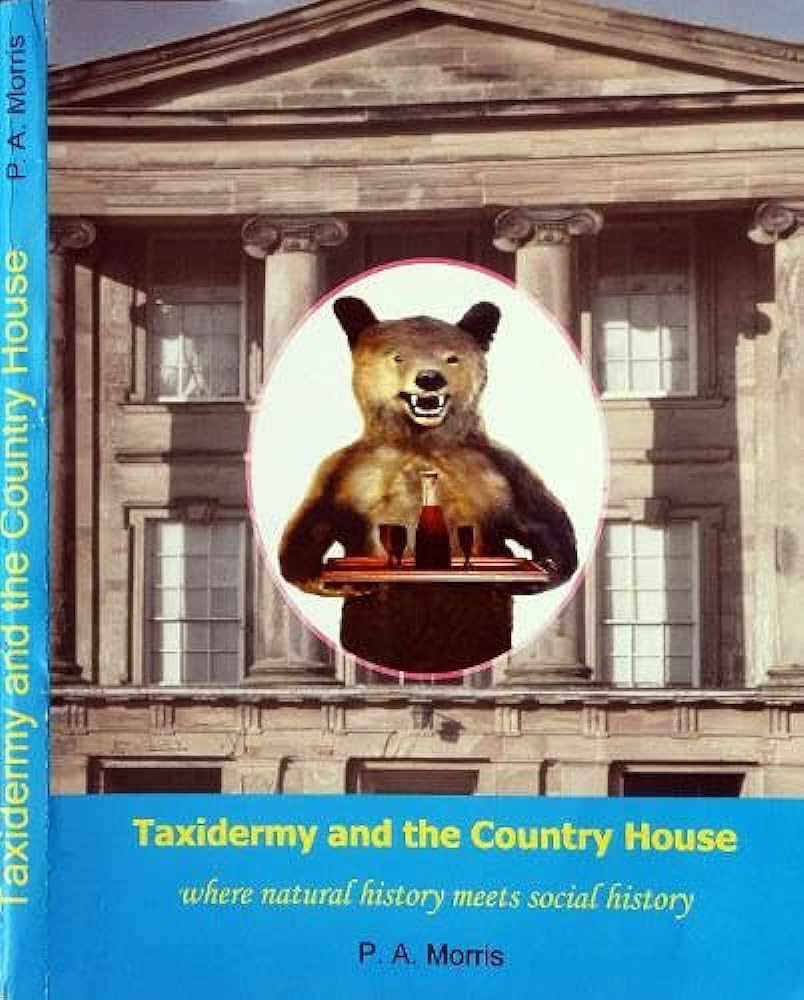

Taxidermy and the country house: Where natural history meets social history by P.A. Morris is published by MPM Publishing. Ascot, Berkshire, 2023.

References

Marvin, G., 2011. Enlivened through memory: Hunters and hunting trophies. In: The afterlives of animals: A museum menagerie. Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, pp. 202-218.