By Lu Allington-Jones (Senior Conservator), Wren Montgomery (FTIR Specialist) and Emma Sherlock (Senior Curator), The Natural History Museum, London UK

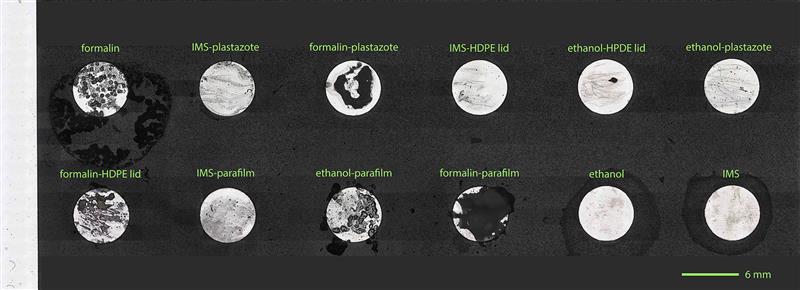

Many years ago, we undertook some research into a suitable replacement for cotton wool as bungs for vials holding small fluid-stored specimens. In 2008 we placed samples of Parafilm MTM, white Plastazote® LD45 and colourless HDPE (high-density polypropylene) lids in 10% formalin, 100% ethanol, and 80% IMS (Industrial Methylated Spirit, aka Industrial Denatured Alcohol) and allowed them to steep for 3 years. We undertook visual inspections, pH tests and FTIR analysis and concluded that Parafilm MTM was an unsuitable replacement, but that the other materials had undergone no change and had caused no contamination of the host fluids.

We decided to revisit the samples after an additional 11 years on a south-west facing sunny lab windowsill, for a total of over 14 years of storage in the various fluids.

Method

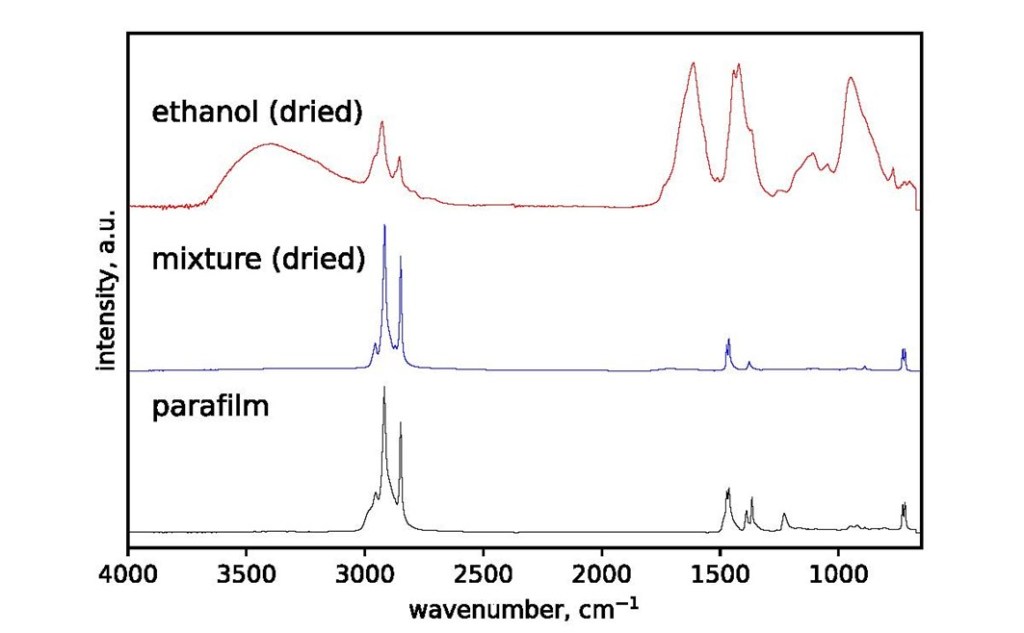

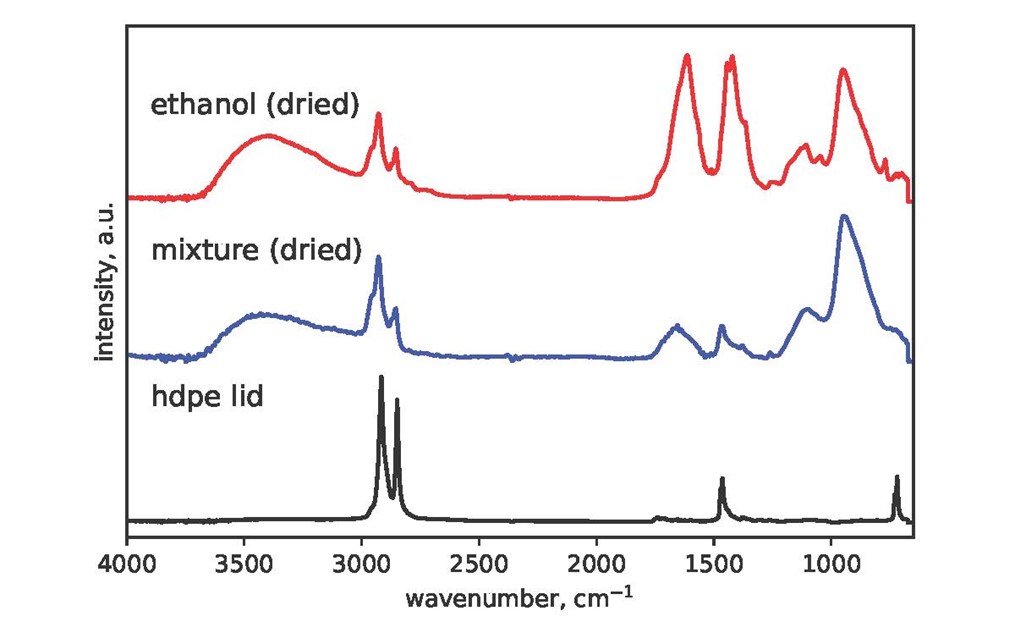

Analysis by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was undertaken by completely evaporating 50 ml of each storage fluid (9 samples, plus samples of the pure fluids) to dryness on a silver-coated glass slide over 5 months and measuring this residue using a Ge-tipped microATR (attenuated total reflectance) accessory on an iN10mx FIR microscope from 500 to 4000 cm-1 at 4 cm-1 spectral resolution. Reference spectra of the Parafilm MTM, Plastazote® and HDPE lid were collected directly from samples. Spectral analysis was performed to determine whether the spectra of the residues of the mixtures were single- or multi- component.

Results

Disappointingly, the Plastazote® has contaminated the IMS storage fluid. It is unclear whether this is due to crumbling or dissolution, and the levels were very slight compared with the Parafilm MTM residues, but any deterioration at all is a concern. There was no detectable contamination of the ethanol by Platsazote®, implying that the deterioration when stored in IMS is caused by (or accelerated by) either the water or the methanol. Due to the abundant formation of an analytically unamenable residue in all cases, the formalin samples could not be analysed using the method in this study. Acidity was measured using Whatman indicator paper. Readings for all samples were found to be around pH 6 to 6.5.

Table of results

| Fluid | Packing material | Contamination detected under FTIR |

| IMS | Lid | No |

| IMS | Plastazote® | Yes |

| IMS | ParafilmTM | Yes |

| Ethanol | Lid | No |

| Ethanol | Plastazote® | No |

| Ethanol | ParafilmTM | Yes |

Conclusion

We uphold our previous conclusions that ParafilmTM is an unsuitable medium for fluid preserved specimens and that HDPE lids and Plastazote® bungs can be useful when transporting individual vials on loan to other institutions. We now know, however, that Plastazote® is NOT suitable for long term storage in IMS and we would only recommend its use in fluid-stored specimens for up to 3 years. HDPE lids are the only material tested which has proved stable for up to 14 years immersion, with flexibility retained and no detectable contamination of storage fluids. Of course, this was also a representative of a worst-case storage environment – our collections are stored in the dark and at lower, much more stable, temperatures. The deterioration of packaging materials is presumably much slower in these conditions than on a sunny windowsill.

Please note that there are many types of preservation fluids used to store specimens and only three were trialled here. Other recipes could have adverse effects on HDPE lids.

Some of the original samples and liquid have been left in place, and so the experiment continues…

To read more, please see the original research:

Allington-Jones, L. and Sherlock, E. 2014. Snagged setae: Evaluating alternatives to cotton wool bungs for liquid-stored specimens Collection Forum 28(1-2): 1-7. doi: 10.14351/0831-4985-28.1.1

Artikel ini sungguh informatif! Saya menghargai kedalaman informasi yang diberikan.kunjungi Telkom University

LikeLike

Pingback: NatSCA Digital Digest – February 2024 | NatSCA