Written by Jack Ashby, Assistant Director of the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge.

One way that museums can decolonise their collections is to celebrate the true diversity of all the people that were ultimately responsible for making them. We often say things like, “This specimen was collected by Darwin”, or whichever famous name put a collection together, when in reality we know that often they weren’t actually the ones who found and caught the animal.

Museums can be rightly proud of their “hero collections” and the famous discoveries represented by them. Acknowledging that they did not work alone does nothing to diminish their accomplishments. We just need to make clear that other people made enormous contributions to their successes, and celebrate them too.

Undeniably, natural history museums have overwhelmingly celebrated dead white men. A major strand of decolonisation work is to show that a greater diversity of people are, in fact, represented in the history of our collections. But in reality, their contributions are rarely documented.

The Malay Teenagers Who Collected Wallace’s Birds

Lately, I’ve been looking at the collection of birds here at the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge, that Alfred Russel Wallace brought back from his eight-year voyage to the Malay Archipelago. Any museum with Wallace material considers it among their treasures. He co-discovered evolution by natural selection, added mountains of invaluable specimens to museums worldwide, and founded entire scientific disciplines based on his interpretations of what he saw. And he gives a lot of credit to the people of colour who collected much of his material.

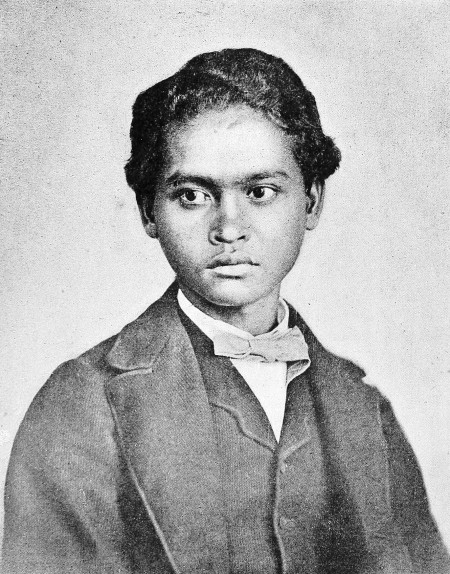

Although Wallace certainly does not name every collecting assistant, a Sarawak teenager named Ali – who joined the voyage when he was probably just 15 – was perhaps his most trusted expedition-member and closest companion. And a 16-year-old named Baderoon from Celebes also provided instrumental contributions to his collections (Van Wyhe & Drawhorn, 2015). Wallace respected them, their insights, wishes and their Islamic faith, and wrote openly about their part in his accomplishments.

In Cambridge, we have what appears to be Wallace’s “personal” specimen of Wallace’s standardwing bird-of-paradise Semioptera wallacii, a species which Wallace is famous for “discovering” on this voyage, at around the time the theory of natural selection came to him on his malarial sick-bed. However, in his published travelogue, The Malay Archipelago, Wallace himself wrote:

“Just as I got home I overtook Ali returning from shooting with some birds hanging from his belt. He seemed much pleased, and said, ‘Look here, sir, what a curious bird,’ holding out what at first completely puzzled me. I saw a bird with a mass of splendid green feathers on its breast, elongated into two glittering tufts; but, what I could not understand was a pair of long white feathers, which stuck straight out from each shoulder. Ali assured me that the bird stuck them out this way itself, when fluttering its wings, and that they had remained so without his touching them. I now saw that I had got a great prize, no less than a completely new form of the Bird of Paradise, differing most remarkably from every other known bird”. (Wallace, 1869)

It’s clear that not only did Ali collect the first specimen of the species (which we can be confident is one of the ones we have in Cambridge) and realised that it was unusual, but also provided details of its natural history. Nonetheless, the world gave Wallace the credit. According to Wallace’s journals and published accounts, it was commonplace for Ali to make such contributions (Van Wyhe & Drawhorn, 2015).

The Wallace’s standardwing bird-of-paradise at the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge – most likely the specimen that Ali first collected for Wallace, described in The Malay Archipelego. It is one of the syntypes (the specimens used to formally describe the species) [UMZC 27/Para/20/a/1] © University of Cambridge

Ali was with Wallace for almost the entire voyage, and collected many if not most of the 8,050 birds Wallace sent back to Europe (and prepared the skins of many more he didn’t shoot himself). Ali is therefore represented in the tens of museums worldwide with “Wallace” specimens.

Heroes and Villains and Nuance

Despite Wallace’s respect for Ali and many of the other Malay collectors he references, at times Wallace’s writing exemplifies the deep-set colonial view of naturalists and explorers of the time.

The king bird-of-paradise at the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge – most likely the specimen that Baderoon collected for Wallace, described in The Malay Archipelego. [UMZC 27/Para/2/a/10] © University of Cambridge

“I had obtained a specimen of the King Bird of Paradise (Paradisea regia) … The emotions excited in the minds of a naturalist, who has long desired to see the actual thing which he has hitherto known only by description, drawing, or badly-preserved external covering — especially when that thing is of surpassing rarity and beauty, require the poetic faculty fully to express them. The remote island in which I found myself situated, in an almost unvisited sea, far from the tracks of merchant fleets and navies; the wild luxuriant tropical forest, which stretched far away on every side; the rude uncultured savages who gathered round me, — all had their influence in determining the emotions with which I gazed upon this ‘thing of beauty.’ I thought of the long ages of the past, during which the successive generations of this little creature had run their course — year by year being born, and living and dying amid these dark and gloomy woods, with no intelligent eye to gaze upon their loveliness; to all appearance such a wanton waste of beauty. Such ideas excite a feeling of melancholy. It seems sad, that on the one hand such exquisite creatures should live out their lives and exhibit their charms only in these wild inhospitable regions, doomed for ages yet to come to hopeless barbarism; while on the other hand, should civilized man ever reach these distant lands, and bring moral, intellectual, and physical light into the recesses of these virgin forests, we may be sure that he will so disturb the nicely-balanced relations of organic and inorganic nature as to cause the disappearance, and finally the extinction, of these very beings whose wonderful structure and beauty he alone is fitted to appreciate and enjoy.” (Wallace, 1869)

“beauty he alone is fitted to appreciate and enjoy”. Wallace is suggesting that the people of the Aru Islands could not recognise their aesthetic beauty, nor had the “intelligent eye[s] to gaze upon their loveliness”. In the emotional, evocative sweep of a pen, Wallace dismissed the experiences, understanding and knowledge of the Indigenous people living alongside the birds, in a way which many Wallace fans may find disquieting.

In decolonisation work it can be tempting to either build up people as heroes who valued the contributions of a diversity of people, or knock down them down as racist villains. However, from the pair of quotes above, we can see that it’s probably more nuanced than that. At times, individuals wrote things that suggest they saw their local collaborators as equals, while at other times their words are deeply problematic.

It’s unfortunate, because not only is most specimen documentation inadequate for telling the truths that would allow museums to celebrate a more diverse group of people who contributed to the history of their collections, but the accounts we do have access to aren’t necessarily trustworthy.

But we do have to try, otherwise museums aren’t telling the stories truthfully. Looking for the Alis and Baderoons in our collections might help more people realise that – as well as all the dead white men – people like them played vital roles in the science and the history on display. And that museums are about them too. To fail to do that is a gross underestimation of museums’ relevance.

References

Van Wyhe, J. & Drawhorn, G. M., 2015. ‘I am Ali Wallace’: The Malay Assistant of Alfred Russel Wallace. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 88, Part 1(308), pp. 3-31.

Wallace, A. R., 1869. The Malay Archipelago. London: Macmillan and Co..

With thanks to Mike Brooke, George Beccaloni and Andrew Berry for their advice on matching Cambridge’s specimens to Wallace’s notes. And to the Natural History Museum, London, for making scans of Wallace’s field-notes available online.

I am very disappointed by this article and surprised that a curator of natural history specimens clearly does not understand what it is to ‘discover’ a new species. By new species we mean a species new to science. New to taxonomists – not new to local people who have known it for hundreds of years. Wallace discovered the Standardwing in this context. Ali was no taxonomist, could not read or write and had no understanding of the taxonomy of Birds of Paradise. Before you jump on the ‘decolonising’ bandwagon, get your facts straight.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi George

I’m a little taken aback by the strength of the language in your comment, but to clarify, I think you are suggesting I said something that I did not. I wasn’t suggesting that Ali was ultimately responsible for the taxonomic description of the standardwing (and, as you know – since George Grey published the scientific species desciption – nor was Wallace), but simply that Ali played a key role in its discovery. He caught the first specimen and helped Wallace understand its natural history. And indeed that Wallace himself made that clear in his writing.

The point here is that we could do more to celebrate the wider diversity of people who made major contributions in the history of science, like Ali (who himself was not a local collector with a longterm knowledge of this species, since he came from Sarawak not Maluku where he caught the specimen). This doesn’t need to diminish Wallace’s massive legacy. In this way, decolonisation is additive, not destructve.

Thanks again for your advice on the labels.

Jack

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Jack. Just saw your reply and I don’t think you understand… When Ali collected the first specimen of the Standardwing on Batchian island (but see below) it was new to him, but he had no way of knowing whether or not it was new to science. Only Wallace knew that the species had not yet been described and named by ornithologists, so it was Wallace who discovered the species, not Ali. Local people must have discovered this bird hundreds of years ago, but we are talking here about discovery in the context of *science*, not personal discovery. Curiously, both Ali and Wallace were in ‘foreign’ countries at the time of the ‘discovery’, so your argument falls down somewhat!

Anyway, as you say the decision to name it after Wallace was made by George Gray. As you know taxonomists are at liberty to choose whatever names they like for species new to science, whether it be a place name, name of a mythological being, a local name, name of their favourite pop singer etc. Gray probably did not know who had collected the first specimen and probably chose to honour Wallace, because Wallace was an ornithologist and had recognised that the species had not previously been described by ornithologists. Ironically, there is some doubt as to whether it was really Ali who collected the first specimen, as the notes Wallace made about this in his Malay Archipelago Journal at the time, do not mention Ali. It is entirely possible that Wallace misremembered the event in question and falsely credited Ali when he published an account of it 11 years later in his book “The Malay Archipelago”.

LikeLike

Hi George

I see you’ve not been tempted to adjust the tone of your comments. As I said, the point I’m making – which I don’t think is hard to demonstrate (and I’m not sure why anyone would argue against it) is that Wallace has received all the credit for the the ‘discovery’ of this species (I’m putting discovery in quotes to demonstrate that western science almost never ‘discovers’ species, as they are obviously already well known to the people who live alongside them – and despite your comment above, I’m clear that I know that Ali and Baderoon are not from the sites of these ‘discoveries’). However, Wallace himself is explicit that Ali is responsible for him first coming to know the species, and that Ali describes aspects of its natural history. The credit should obviously be shared. At no point do I say that it shouldn’t have been named after Wallace, but if you are curious, my opinion is that we’re better off not naming animals after people at all.

I would suggest it’s a stretch to raise doubts Ali’s role based on the notion that Wallace didn’t include it in his journal – it was clearly a memorable event for him in the voyage. I’m not sure why anyone would want to inject doubt into this, either.

My motivation is to demonstrate that a wider diversity of people were involved in major developments in the history of science. Traditionally notions of white supremecy have over-written the contributions that other people made to the development of the discipline, and as I hope you’d agree, that’s not helpful for scientific advancement, particularly as it can disenfranchise people from engaging in natural history. Let’s leave it at that, shall we?

LikeLike

Pingback: NatSCA Digital Digest – November | NatSCA

Pingback: CFP: ‘Heroes and Villains in the Anthropocene’ – ANTHROPOLOGY JOURNAL

Pingback: Natural History, Extinction, and Storytelling at the Museum of Zoology – Museum of Zoology Blog

Pingback: Top 10 Blogs of 2020 | NatSCA

Pingback: CFP: ‘Heroes and Villains in the Anthropocene’ – AJ

Pingback: How Do We Commemorate Science and Scientists? The Case of Dilip Mahalanabis – The Wire Science – https://bhartiyanews24x7.com

Pingback: How Do You Do Decolonial Research in Natural History Museums? | NatSCA