Written by Dr Jamie Maxwell, Collections Assistant, National Museum of Ireland, Natural History.

Not every job takes you to a windswept beach on Ireland’s west coast to recover the head of a stranded True’s beaked whale calf. But then again, my past year as a Collections Assistant at the Natural History Museum in Dublin has been anything but ordinary. As we collected the head of the slightly decomposed whale calf, I was reminded of my previous fieldwork experiences, mainly on research cruises during my academic career. Before joining the museum, I spent a decade in education and research as a marine biologist, specializing in deep-sea invertebrates. During that time, I not only investigated freshly collected specimens but also engaged with museum collections. It wasn’t until I became a collections assistant at the National Museum of Ireland, Natural History that I became fully immersed in the day-to-day workings of a museum. Much of the past year was taken up with decanting the contents of the Merrion Street building in preparation for renovation. In this blog, I’ll explore how decanting a museum is remarkably like being involved with a research cruise.

Figure 1. Before I embarked on my second research cruise on the RV Celtic Explorer, one of the Irish Marine Institute’s research vessels. © J Maxwell

I have been fortunate enough to spend nearly 100 days at sea on research vessels on expeditions ranging from 2 weeks to nearly 2 months. I sailed across the Atlantic and went to the Southern Ocean, but never did I think that when I got the job in the Natural History Museum in Dublin it would be so similar to these experiences. Of course both involve biological specimens, just at different stages of their scientific journey, as all museum specimens had to be collected at some point. But beyond that the tasks were nearly identical in both workplaces, all specimens had to be photographed, categorized, documented and carefully packed. While this is probably not too surprising as protocols are similar across all science fields it was the similarity in team dynamics, ethos and humour which were the most striking similarities for me.

Figure 2. Mirrored experiences, one wet, one dry. Left, Launching the Holland 1, the Irish Marine Institute’s Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV), to explore the Whittard Canyon two kilometres below the surface. Right, Removing a grizzly bear from the Natural History Museum in Merrion Square, Dublin. © J Maxwell

Being confined on a research vessel with a small group of people for weeks at a time creates a high-pressure and occasionally stressful work environment. However, it also fosters camaraderie and teamwork. During the decant, the stress levels may not have been quite as high, plus I got to go home at the end of each day, but the sense of camaraderie within the team reminded me of the dynamic on a research cruise. Both jobs involve a small working team, confined to a single space, focused on a shared goal that demands dynamic thinking, collaboration, and a constant readiness to expect the unexpected! Lowering nearly three-quarters of a ton basking shark from the museum ceiling was oddly reminiscent of hauling in a trawl net in the middle of the night in the Weddel Sea. There was the same team effort, just as many ropes and pulleys, and a sense of excitement with a small slice of fear. All that was missing was a moving floor, and freezing sea spray!

Figure 3. Winches, pulleys and ropes. Left, Recovering an Epi-Benthic Sledge (EBS) in the middle of the night in the Weddell Sea, Antarctic. Middle, Lowering the Basking Shark from the ceiling of the Irish Room in the Natural History Museum Dublin. Right. Retrieving a weather buoy 500 km off the west coast of Ireland. © J Maxwell

There is also an element of “you don’t have to be crazy to work here but it helps”. Cabin fever is most definitely a feature, and in my experience the best way to combat it is to embrace it and channel it into a fun and silly task. These tasks will very often become a group effort. Such as a “Bake Off” style crisp sandwich competition (salt and vinegar, brie cheese and strawberry jam won), or the creation of a deep-sea Mavel-esque universe stemming on an observation of two squat lobsters that appeared to be bickering on a coral complete with comic strips, screenplays, merchandise designs and folk songs, or the renaming of yoga poses to marine themes. During the decant, there were times when morale was low, or people were just tired after a long week. It was in these moments that one found humour in terrible taxidermy, reimagined a stillage as a bus and all the birds of prey within it were on a trip and were too lazy to fly, or constructing a sarcophagus for a mummified mouse.

Figure 4. The final resting place of a museum mouse. A sarcophagus created for a long dead mouse found behind a cabinet, one of the “side projects” that kept the mood up. © J Maxwell

Once objects were safely extracted from walls, cases or ceilings, they all had to be packed up and prepared for transport to storage. In many ways, this process is remarkably like preparing for and demobilizing after a research cruise. In both contexts, objects must be packed efficiently and safely, protected from damage, and remain traceable throughout their movement. Packing a Peregrine falcon or a bat skeleton requires the same care and planning as transporting delicate scientific equipment at sea or ensuring biological samples return to shore intact. Whether the goal is to prevent damage from the roll and pitch of a ship or from speed bumps on Dublin’s roads, each object must be individually assessed and stabilized, often requiring creative solutions.

Accurate documentation is another essential aspect of both specimen collection and museum practice. In the field, detailed data collection ensures that specimens can be properly identified, contextualized, and used in future research (or indeed as future museum specimens). In the museum, documentation underpins object tracking, condition reporting, and interpretation. Recording metadata, maintaining logs, and managing sample data have really helped me to understand and best support the work of my documentation colleagues.

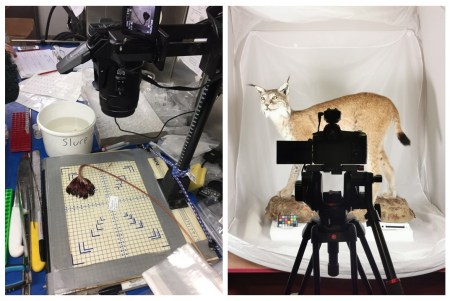

Figure 5. Fresh and faded, documentation of specimens at sea and on land. Left. Documenting a Umbellula sp. coral, collected from the Irish Deep Sea. Right. Documenting a Eurasian lynx, after it had been removed from its cabinet, before it was prepared for transport to storage. © J Maxwell

Mistakes happen, let’s be honest they inevitably do, especially when dealing with large volumes of specimens/objects moving through different sets of protocols, identifying the mistakes as early as possible is essential. While I would obviously prefer mistakes to not happen in the first place, backtracking through data logs or physically searching for lost specimens appeals to my inner detective. So, when I had to unpack a box I had packed hours earlier, or trawl through the photography log to see if we had in fact packed that one unaccounted for specimen, I could not help but flash back to the time on the ship when the same situation had arisen. We had to unpack and repack a -80 freezer as quickly as possible at 4am in the morning to see if the bamboo coral that was on the collections log, was on the processing log but not on the freezer log, was indeed in the freezer and had just slipped through the final log unchecked. That sense of relief when an error has been corrected is universal. Another thing that a mistake can foster in team environments such as on a research vessel or the museum in my experience is a shared responsibility and a team pulling together to fix them without blame.

And finally as the last object was removed from the building (ignoring the elephant and basking shark which were too big to fit out the door, but let’s not allow that interrupt a ceremonial ending) there was that all too familiar sense of joy, relief, and sadness all rolled into one, the same feelings I would get when I walked down the gangplank back onto the dock. Thankfully this feeling was not combined with the onset of land sickness (yes I get land-sick but have yet to be sea-sick) although I may have been swaying a little bit after the celebration drinks. And then there is the planning for the next part. After a research cruise, it’s ensuring everything gets to where it needs to go, assessing what has been collected and beginning the planning for the taxonomic and/or lab work that follows. In the exact same vein, all the objects removed from the museum now need to be cleaned, properly shelved and their taxonomic and personal histories researched and document, all in preparation for them to set sail in the museum once again.

Figure 6. Signed, sealed and soon to be delivered. Seal pups prepped to be removed from the museum and brought to the storage facilities where they will be cleaned and shelved. © J Maxwell

Over the past year, I’ve come to realise that working in a natural history museum isn’t all that different from life at sea, minus the waves and waterproofs. From packing specimens to logging data, navigating team dynamics, and finding humour in the chaos, the parallels between research cruises and museum decanting have been uncanny. It turns out that whether you’re hauling a trawl net or lowering a basking shark from a ceiling, the tools, teamwork, and occasional madness are strikingly familiar. And honestly, I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Pingback: NatSCA Digital Digest – October 2025 | NatSCA