Unraveling an ancient mystery

Picturing the world of the prehistoric is often likened to a jigsaw puzzle: one in which each new piece starts a whole new puzzle. Your pieces are scattered across all the museum stores in the world or weathering out of the ground. The quality is variable and some of the pieces are warped. In some cases we get lucky and find an immaculately preserved specimen, like the ones being uncovered in China, with evidence of soft tissue still preserved. In other cases, we must rely on osteological correlates in living animals to work out what’s going on.

Palaeontologist Mark Witton recently wrote a post about a group of predatory dinosaurs called abelisaurs. These animals have a rough, cornified texture to their skulls. Living animals with a comparable bone texture usually have hardened, reinforced skin. Hippopotamus faces regularly endure blows from rival hippo teeth and, while scarring occurs, lasting damage is usually avoided. Some theropod dinosaurs* show bite scars on their faces which suggest that something similar was happening with these too. Hardened, armoured skin would be very useful here. However…

We are used to thinking of armour in the mediaeval knight or Kevlar sense of the word. This is not quite how tough hide works in living animals and apparently not for extinct ones either.

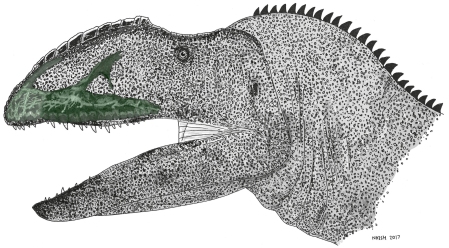

Neovenator salerii, showing neurovascular regions. Image property of Darren Naish, shown here with permission.

Enter Neovenator

A new paper, published today by Chris Tijani Barker and colleagues, point to a network of sensory canals in the snout of Neovenator salerii – an early Cretaceous allosauroid theropod. The type specimen, held at the Museum of Isle of Wight Geology, has all the hallmarks of abelisaur-style facial armour but also sensory features similar to those found in crocodiles.

Crocodile facial tissue is both tough and sensitive, like a gauntlet that can read Braille.

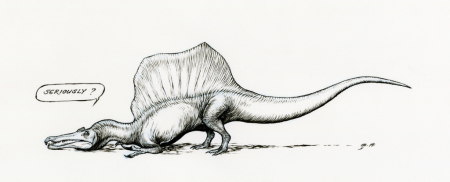

It’s most intriguing because, in 2014, Nizar Ibrahim and colleagues highlighted sensory pits in Spinosaurus as one of a suite of characteristics that demonstrate aquatic behaviour. That paper ricocheted around social media like a gunshot, with many critiques of the revised limb proportions of Spinosaurus

New-look Spinosaurus. Image property of Natee Himmapaan, shown here with permission.

but very little attention was paid to the sensory pits – until now. Neovenator is a clearly terrestrial carnivore, built for land-based activity, yet it has these sensory features on its snout which allow the face to respond to subtle touch stimuli. The paper goes into other examples of animals that have such protective face coverings and delicate sense of touch: duck beaks to name but one. I shan’t steal the paper’s thunder by reciting them all here – it’s well worth a read if you’re curious. One of the paper’s contributors, Darren Naish, has also written up the discovery here.

Perhaps we will see another revision of the Spinosaurus material when the long-awaited monograph comes out, now that yet another feature has fallen into the “not necessarily aquatic” category, we can only wait and see. Regardless, Neovenator is an interesting specimen in its own right and I’m sure it has even more secrets to yield.

* I’m explicitly not naming that species: It already gets the lion’s share of press coverage and is mentioned in unrelated press articles, it’s about time it was ignored in related ones.